Dalberg uses cookies and related technologies to improve the way the site functions. A cookie is a text file that is stored on your device. We use these text files for functionality such as to analyze our traffic or to personalize content. You can easily control how we use cookies on your device by adjusting the settings below, and you may also change those settings at any time by visiting our privacy policy page.

Youth mental health is a pressing global concern, transcending borders and economic divisions. In our rapidly changing world, young people face unique challenges that significantly affect their mental well-being. Emerging threats like pandemics and climate change have left many feeling despondent about the future, with nearly 59% of young individuals expressing concern about climate change globally, according to a 2021 Lancet report.¹ These emotions can hinder daily functioning, impacting their overall quality of life. In our recent work, supported by UNICEF Innovation, with young people in Bolivia and Nigeria, we employed a Human-Centered Design (HCD) research approach to uncover their deepest worries, barriers to accessing mental health support, and their vision for their mental health future.

In low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), where limited access to mental health services combined with economic and environmental challenges, addressing youth mental health is paramount. Beyond climate change, recent global economic crises have forced many young people into adulthood prematurely. Additionally, the pervasive influence of social media exacerbates these issues, fostering a sense of shame regarding income and social status.

Access to mental health care remains minimal, particularly in LMICs, where a severe shortage of mental health professionals prevails. Alarmingly, only 1 in 27 individuals with depressive disorders in LMICs receive minimally adequate treatment. Comprehensive national mental health policies and programs are urgently needed, but to effectively reach youth, a profound understanding of their diverse experiences within their specific contexts is essential.

“We are moving from childhood to adulthood, we are struggling a lot, trying to be social, trying to be present, dealing with school, we need to make major decisions with our career and everything and that is why we are in a moment where our mental health is vulnerable”

– Young Nigerian influencer

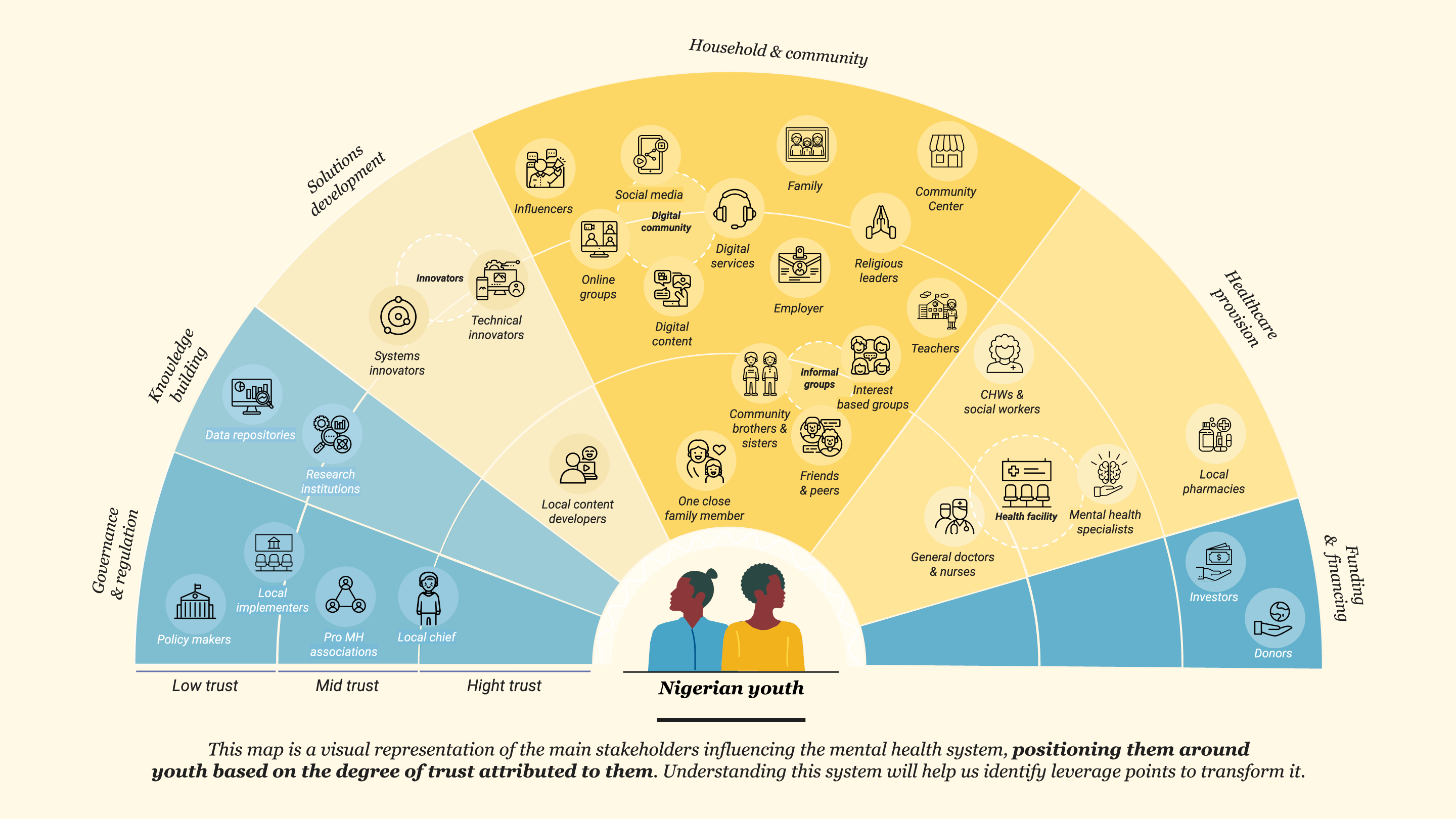

Given the stigma surrounding mental health issues, we adopted a participatory approach, using creative tools like trust maps and visioning exercises to foster open dialogue on emerging mental health topics:

Through this process, we unearthed 5 insights that paint a portrait of youth mental health systems in LMICs:

1. Stigma Colors the Perception of Mental Health

For many young people, mental health is closely linked to spiritual or psychological afflictions. This deep-seated belief often prevents them from openly discussing their struggles or seeking professional help due to the fear of stigmatization. In Nigeria and Bolivia, mental health challenges are often viewed as spiritual issues that can be addressed through prayer, or as severe psychiatric disorders afflicting only a few members of the community. This outlook discourages young people from seeking help and pushes them towards unhealthy coping mechanisms.

“It is often embarrassing to talk about mental illness. They call us crazy, I would like to help others who like me have schizophrenia so that we can open up and understand more about each other.”

– Bolivian young man

“You do not have independence to afford or have money to seek help. When you ask your family and you’re coming out to them about the condition, families would turn you to spiritual homes and traditional groups”

– Nigerian mental health professional and influencer

2. Youth Struggle to be Heard in Society

Cultural norms that frequently dismiss emotions leave young people feeling ashamed and unheard by their elders when they reach out for support. Both Nigerian and Bolivian youth often struggle to recognize their feelings and emotions, with daily survival challenges, demanding family systems, and navigating their own sexuality overshadowing their mental well-being. This context fosters feelings of shame and inhibits their ability to openly express emotions, causing them to suppress their feelings and hesitate to reach out to adults for help.

“In our community seeking help is complicated. Sometimes we go to our parents, but they don’t believe us, they don’t support us, they discourage us, they tell us to stop talking about it.”

– Bolivian Indigenous young woman

“If a young person exhibits sad behavior, they are usually taunted, ‘what have you seen in life to be tormented with the world’s burden’. Mental health burden is not acknowledged for young people”

– Health Specialist, UNICEF Nigeria CO

3. Support Systems Do Not Go Far Enough

While friends and informal groups have become preferred sources of support, they are often unequipped to provide sustained, specialized assistance when it is required most. Young people experience loneliness during their transition from childhood to adulthood, facing challenges that parents, family members, and teachers often cannot relate to. Informal support groups and belonging to them fill gaps in national systems but may not address deeper emotional trauma.

“[Before coming out] I didn’t feel like I was myself, I felt locked in. But Miss Kelly gave me strength to start talking about my identity. Now my mom supports me, she even comes to marches with me!”

– Young Bolivian person identifying as LGBTQ

“I always to go and talk to them [community brothers and sisters], we have a close connection, they live near my house and I speak to them, whatever advice they give, they are like as god mothers/godfathers”

– Nigerian young woman

4. Access to Knowledge Remains Limited

Knowledge and awareness about mental health remain a privilege, largely determined by factors such as geographic location, family income, religious and cultural backgrounds, gender, sexual orientation, and community attitudes. Even though youth rely on social media for information, much of the content and services available seem distant from local realities, culture, language, and traditions, deeming them in most cases irrelevant.

“Is easy to get internet, but the access to data and tech is different for different regions. Some have no access to tech and hence some of those online services can’t reach by these populations”

– Mental health professional and influencer

5. Lack of Trusted Relationships Strain the System

Many young people withdraw from health centers due to concerns about potential judgment and reprimands from staff. Confidentiality breaches are common, and inadequate training to provide mental health assistance to this demographic compounds the challenges. In both Bolivia and Nigeria, the existing mental health infrastructure is stretched, with more seasoned professionals more readily available in urban areas.

“Adolescents want somebody they can trust; a friend [within the healthcare system], not just a mother. The attitude of health workers is not something that can work with adolescents; they lack empathy and therefore the adolescents turn away from health professionals”

– Adolescent Health Lead, Federal Ministry of Health, Nigeria

A Path-Forward for a Youth-Centered Mental Health System

The young individuals we spoke with in both countries envision a robust and thriving mental health system. They envision a system that involves their communities, fosters their sense of value, creates reliable support networks, actively engages with them through compassionate communities, empowers them to effectively aid themselves and their peers, and encourages their leadership in influencing their mental well-being.

Crucial to this vision is the expansion of support beyond mental health professionals to include parents, teachers, community leaders, and even social media influencers. These figures can help young people recognize mental health concerns and develop strong socio-emotional skills to tackle daily challenges. While digital platforms hold promise in strengthening this support system, it’s vital to actively engage young people in designing these services, addressing potential harms and inequities through a youth-centered approach.

Creating a support system that empowers young people to feel valued and equipped is not just an act of compassion; it’s a matter of upholding their fundamental human rights. Acknowledging that youth mental health is intertwined with our society’s fabric underscores its significance. This issue impacts not only their well-being but also has far-reaching implications for the future of our planet, particularly in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), where these concerns often remain hidden.