Dalberg uses cookies and related technologies to improve the way the site functions. A cookie is a text file that is stored on your device. We use these text files for functionality such as to analyze our traffic or to personalize content. You can easily control how we use cookies on your device by adjusting the settings below, and you may also change those settings at any time by visiting our privacy policy page.

The global health sector is at a pivotal crossroads. With a projected 40–60% decline[1] in Official Development Assistance (ODA) over the next five years, critical health systems in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) are confronting an urgent funding crisis. This anticipated drop is driven by shifting geopolitical priorities, including tightening national budgets and increased aid to Ukraine.

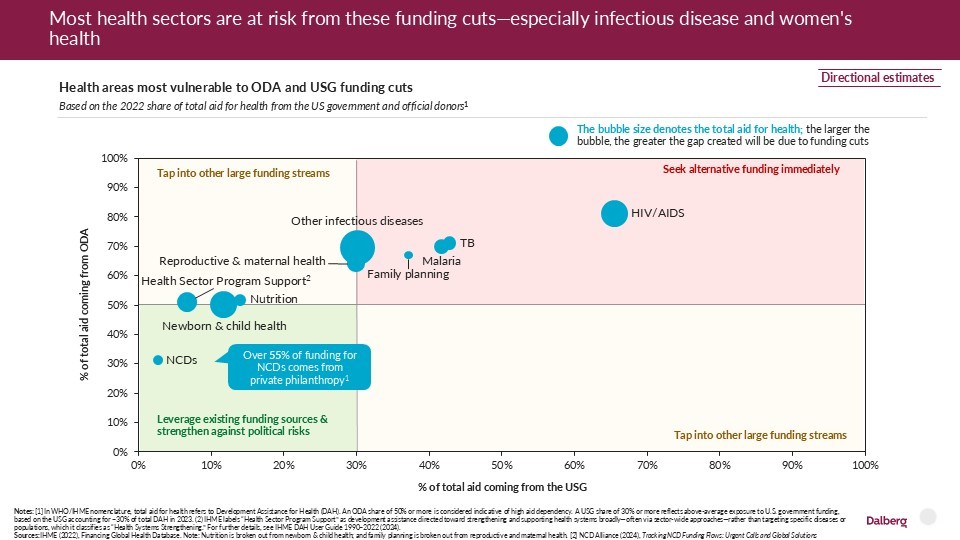

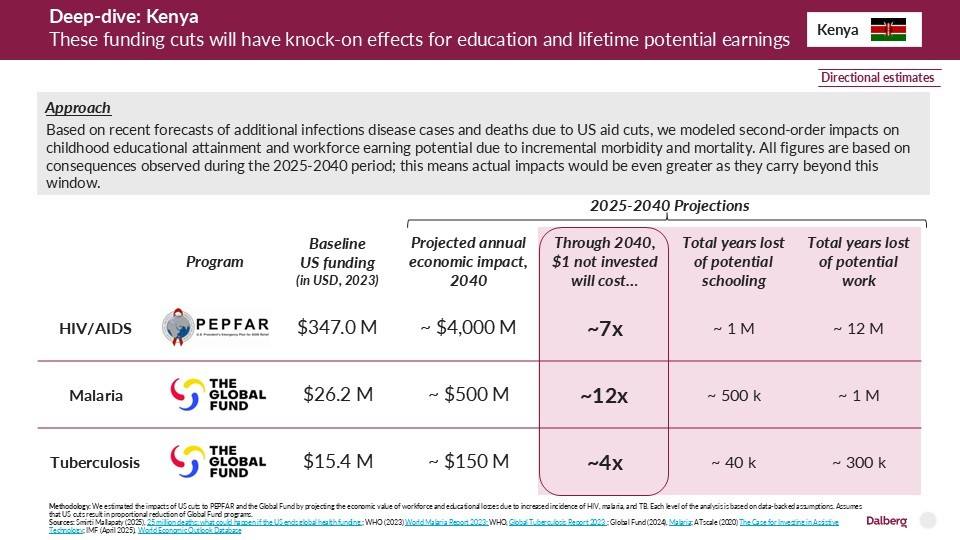

Health areas like HIV, TB, malaria, and maternal health are especially exposed, with more than 70% of their funding reliant on ODA and over 30% from U.S. government sources.[2] Cuts of this magnitude will not only cost lives directly but may lead to further increases in infectious diseases both locally and globally, threatening global health security. In addition, these funding losses carry significant economic consequences. In Kenya, for instance, every $1 not invested in malaria prevention could equate to $12 in lost economic productivity, due to reduced educational attainment and diminished lifetime earnings from preventable illness.[3]

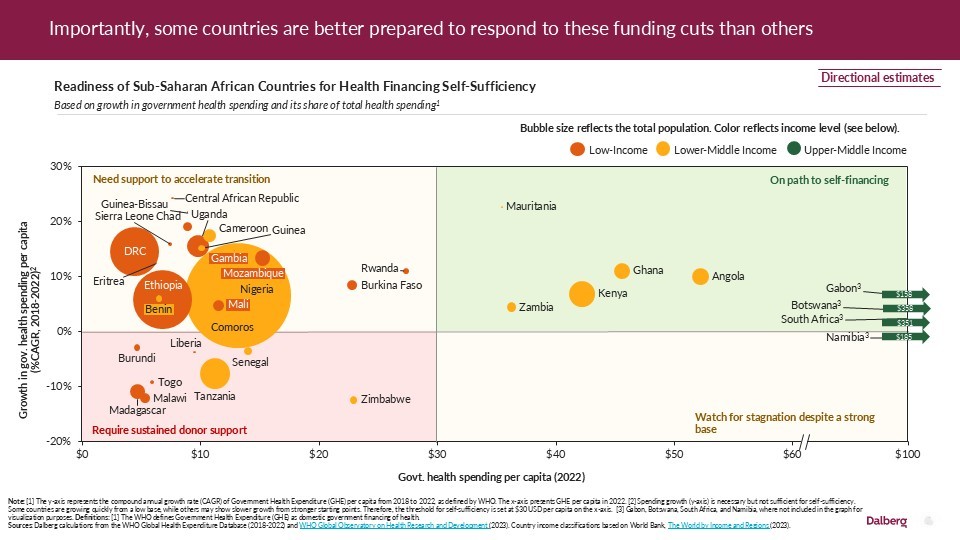

Not all countries are equally vulnerable. Some—including Kenya, Nigeria, and Ethiopia—have increased domestic health spending in recent years and may be better positioned to adapt.[4] However, many LMICs remain far from self-reliance. A new financing approach is needed—one that blends public, philanthropic, and private capital to bridge the emerging gap.

Toward a Resilient Funding Future

Broadly, these funding challenges beg the question: What global health architecture will best serve countries to emerge stronger from these cuts? We must examine how to strategically support countries on their paths to self-reliance and design a global support system that drives towards this.

Replacing lost funding will be nearly impossible. Instead, countries and donors will need to be more strategic in how they raise funds, how they match funds to the most appropriate uses, and how they deploy funds. As a starting point, countries, philanthropists, and development finance actors can:

Tap New Capital

Engage new philanthropists—especially high-net-worth individuals (HNWIs) and family offices in North America, APAC, MENA, and Europe—and faith-based donors, who already play a major role in service delivery across Africa, providing up to 70% of care in some regions. Both of these funding sources are projected to grow in the years ahead and offer untapped potential for cross-border funding.[5]

Unlock Private Capital through Blended Finance

With a historic 3.3x leverage ratio, blended finance has the potential to crowd in commercial capital at scale.[6] Institutions like the International Finance Corporation (IFC), the Dutch Entrepreneurial Development Bank (FMO), and the U.S. International Development Finance Corporation (DFC) are already active, supporting health investments that would otherwise go unfunded. Key sectors like basic health services—often delivered by under-resourced SMEs—stand to benefit most.

Invest for Impact

Direct resources to high-ROI areas such as system capacity (including workforce and infrastructure) and digital health. These investments not only save lives but consistently deliver economic and operational returns—especially when supported by strong governance and national ownership. For example, digital tools that enhance workforce productivity and streamline supply chains have been shown to reduce related costs by up to 50% and save millions of lives through better care coordination.[7]

The Road Ahead

The funding challenges ahead are real—and urgent. But this moment also offers a rare opportunity to redesign global health financing for the better: more diversified, more resilient, and more inclusive of actors beyond traditional donors. Country governments can think about how to raise funds from new sources, including faith-based funding networks; better match blended financing tools to the most appropriate uses locally; and invest in digital transformation. Philanthropists can consider how to help raise capital from new partners, especially among HNWIs and private capital (via de-risking), and use capital towards the highest ROI areas. Development finance actors can continue to look for ways to match their funds to local needs. Together, we can protect health gains and unlock new value for billions.

[1] Dalberg analysis based on announced cuts as of 2025 and OECD (2025) Data Explorer.

[2] IHME (2024), Financing Global Health Database.

[3] Dalberg analysis based on Smirti Mallapaty (2025), 25 million deaths: what could happen if the US ends global health funding; WHO (2023) World Malaria Report 2023; Global Fund (2024), Malaria; (4) ATscale (2020) The Case for Investing in Assistive Technology; (5) IMF (April 2025), World Economic Outlook Database

[4] WHO (2024) Global Health Expenditure Database; WHO (2025) Global Observatory on Health Research and Development

[5] Dalberg analysis based on Giving USA (2025) Giving USA: U.S. charitable giving totaled $557.16 billion in 2023; Johnson (2018) Global Philanthropy Report; Candid (2025) Foundation Maps; World Economic Forum & GAEA (2024) The Role of Corporate Philanthropy in Accelerating Climate and Nature Transitions; Indiana University Indianapolis (2022) Global Philanthropy Indices: Trends & Themes; CECP (2023) Giving in Numbers; Nicol, et al (2022), “The impact of faith-based organizations on maternal and child health care outcomes in Africa: taking stock of research evidence”; Wodon, et al (2014), “Market Share of Faith-Inspired Health Care Providers: Reach to the Poor in Africa”

[6] Dalberg analysis based on Convergence, Market Data – Explorer [accessed May 2025]

[7] Dalberg analysis based on WHO (2024), Going Digital for Noncommunicable Diseases: The Case for Action; VPL (2024), Digital Transformation in the Healthcare Supply Chain; Johnson & Johnson (2021), “How Johnson & Johnson’s Innovative Supply Chain technology Is Helping Transform How We Work—And Live”

The above piece draws on an analysis conducted by Dalberg on the shifting funding landscape for global health and the path forward. For more details, please reach out to Erin: