Dalberg uses cookies and related technologies to improve the way the site functions. A cookie is a text file that is stored on your device. We use these text files for functionality such as to analyze our traffic or to personalize content. You can easily control how we use cookies on your device by adjusting the settings below, and you may also change those settings at any time by visiting our privacy policy page.

Can tourism fuel post-pandemic economic recovery, adequately support livelihoods and spur efforts related to biodiversity protection? A new wave of tourism products shows what is possible. Countries are developing experiences that both conserve plant and animal life and encourage community development, giving hope that tourism could be an important frontier for the future of conservation efforts.

In 2020, tourism suffered what the UN World Tourism Organization called “the worst year in tourism history” due to the Covid-19 pandemic.1 International arrivals dropped by 74% and destinations worldwide welcomed 1 billion fewer people than in the previous year, due to an unprecedented fall in demand and widespread travel restrictions. The crisis has put between 100 and 120 million direct tourism jobs at risk, many of them in small- and medium-sized enterprises.2

At the same time, this unprecedented dip in demand and spending comes with a unique chance to redefine the role of tourism for countries, communities, and biodiversity. It is time to look at tourism growth through the lens of environmental protection and conservation, and to see rebuilding efforts as an opportunity to directly impact climate and habitat health

The Link Between Tourism and Biodiversity Conservation

To date, the financing of the conservation sector—and efforts related to the global frameworks set out to help protect nature—has primarily been supported by charitable funding, with campaigns pitched around broad goals such as “save the planet” or highly specific, non-systemic calls for discrete species or causes, like “save the elephants.” While it is important to raise awareness for an ever-increasing number of issues, these efforts are not enough to match the urgent needs at hand, given the effects of rapid population growth and climate change. Bridging the financing gap will require the use of more systemic approaches.

Tourism could serve as an important—and largely underleveraged—conservation lever. Since 2012, more than 1 billion people have traveled as tourists to areas known for their natural beauty and wildlife.3 In some regions, the natural world is the single biggest draw—such as in Africa, where it is estimated that 80% of trips made to the continent are for wildlife watching.4

Pre-pandemic, safari and wildlife tourism generated $12.4 billion in annual revenue for South Africa, Botswana, Kenya, Rwanda, Tanzania, Uganda, and Zambia combined.5 In these places, the tourism sector is a key contributor to protected area (PA) management via park fees and lodge/camp concession revenues and licenses.

Economic proceeds from tourism receipts form the core of many governments’ biodiversity conservation budgets. As such, biodiversity conservation is highly dependent on the success of ecotourism businesses. Tourism not only brings in important tax revenue and foreign exchange for governments, but also acts as an economic multiplier that addresses the economic needs of communities and helps limit impact on natural habitats.

Take the example of Rwanda, where a government increase in the price of permits to trek to see silverback gorillas has limited human disruption in the gorillas’ habitat while generating sufficient revenue for habitat conservation and community development. These conservation efforts have led to an emergence of eco-tourism enterprises partnering with the community to improve livelihoods. At the Sabyinyo Community Livelihoods Association and Governor’s Camp, community members own the lodge and receive a proportion of the lodges’ revenue. The alliance has transformed the community’s economy generating ~$2.9 million in the past decade.

Such transformation has also incentivized the community to protect the mountain gorilla and its habitat,6 including investments from the Ellen DeGeneres Fund that support global conservation efforts for endangered species.7 Ellen DeGeneres recently launched a multi-purpose campus in Northern Rwanda, to amplify its mission of conservation, protect and study gorillas, train the next generation of African conservationists, and build the conservation capacity of local communities.8

The Public-Community initiatives in the Okavango delta in Botswana also demonstrate the effectiveness of combining tourism revenue and community involvement. There, the national strategy to promote high-value, low-volume tourism enables the country to manage tourist movement and avoid mass tourism. Moreover, the government requires communities to form community trusts to implement ecotourism projects. Trusts are registered legal entities that enable collective action in conservation and ecotourism development.9 Since 2012, there have been 14 ecotourism organizations in the northwest, and the Chobe districts of the Okavango Delta employed 610 people and generated over $600,000 in revenue.10

Welcoming the Next Wave of Tourism

From community collaboration to the Global Goals, tourism has a critical role to play. Only 0.5% of yearly tourism turnover is needed for the management of a global complete network of protected areas, making the case for supporting a more sustainable recovery for the tourism sector even clearer.11

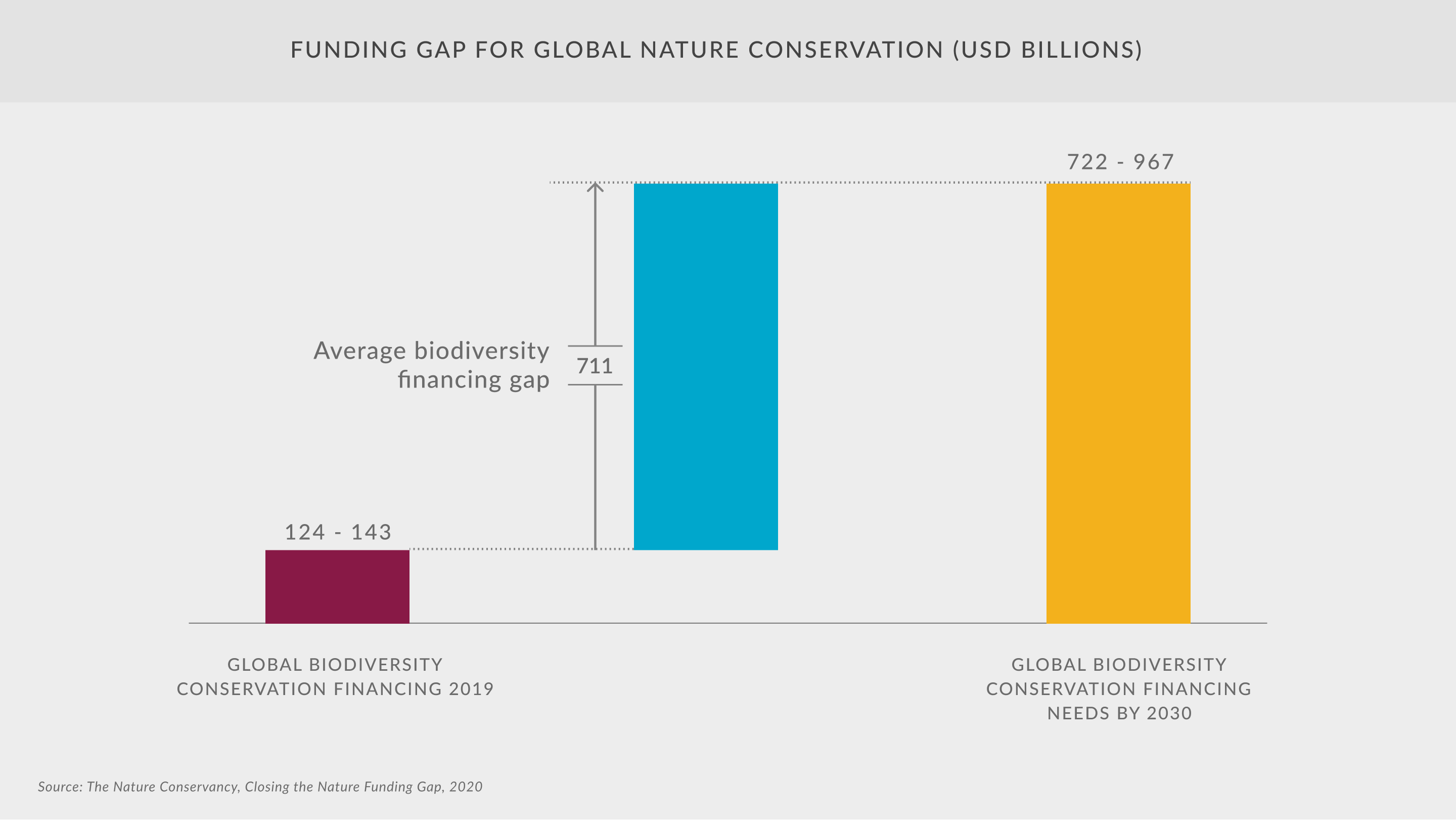

Today, 6% of global nature conservation funding is spent in Africa, which hosts a third of the planet’s biodiversity. In Eastern and Southern Africa, an assessment of more than 282 state-owned protected areas concluded that available funding only satisfied 10-20% of management needs.12 Consequently, as can be seen from the graph below, there is a significant financial gap in meeting global conservation needs. In 2019, biodiversity spending was estimated to be between $124 and $143 billion annually, against the required annual total of $722 and $967 billion.13

Countries across the world have already been capitalizing on the opportunity to leverage tourism for conservation efforts. Examples below show how tourism revenue can be channeled to fund conservation efforts,

- In Nepal, responsible and well-managed wildlife tourism run by the government and tour operators is indirectly providing funds for multiple conservation projects and anti-poaching operations in national parks.14

- A South African national conservation parastatal—which is mainly funded by revenues from ecotourism activities—oversees the maintenance of 22 protected areas. In total, these areas account for 4% of the nation’s landmass.15

- In the United States, birding activities in the Delaware Bay are stimulating investments in curbing the unsustainable harvest of horseshoe crabs by the biomedical industry and protecting the main sources of food for migratory shorebirds.16

Alongside these examples, over the past few decades, a handful of important frameworks for conservation have been spearheaded by governments and civil society to help slow these negative effects. For instance, The Convention on Biological Diversity was drafted by the United Nations in 1990 as a legal instrument for biodiversity conservation and the sustainable use of nature17 In 2015, goal 14 of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) was developed to increase global investment efforts to conserve and encourage the sustainable use of oceans, seas, and marine resources. Additionally, Goal 15 aims to protect, restore, and promote the sustainable use of terrestrial resources while combating land degradation and biodiversity loss.18 These frameworks set out roadmaps for conservation and tourism can play a key role in delivering on SDG objectives if integrated thoughtfully and systemically.

Leveraging Nature-based Tourism for Biodiversity Conservation: Fundamental Actions To Consider for Post-pandemic Recovery

We believe now is the time to increase incentives and improve investments into strengthening nature-based tourism opportunities. As the world recovers from the effects of the pandemic, a path can be shaped that will strengthen the tourism sector in a way that contributes to biodiversity protection.

This work starts with re-thinking travel products and building out the investment ecosystem:

- Leverage existing interests in nature-based tourism experiences: As the tourism sector recovers from the effects of the Covid-19 pandemic, it is likely that travel patterns will change. The already-increasing trend for sustainable travel and appetite for nature-based experiences can be leveraged to influence post-Covid-19 travel patterns towards more biodiversity-friendly experiences and products.19

- Create an investment framework for investors: More investors are seeking green investments, most of which are focused on carbon-reduction projects because their impact is easier to measure. Investors also have an interest in biodiversity investments. Although there are organizations with in-house investment platforms such as NatureVest that support investors, there isn’t a comprehensive investment framework in the space that enables investors to assess the biodiversity impact of their investments, to assess the trade-offs between biodiversity and financial returns, and to compare across investment opportunities. Developing a biodiversity investment framework can give investors the vocabulary they need to increase their investments.

The ground under the tourism sector’s feet has shifted as a result of the pandemic, and now is an opportune time to create bridges across the now-exposed gaps between biodiversity protection and travel experiences. Together with governments, investors, and communities, the stage is set to create a healthier planetary future and a more equitable world for both host countries and their visitors.

Contributing writer: Irene Kinyanguli

-

1

World Travel & Tourism Council (WTTC), Economic Impact Reports, wttc.org

-

2

UNWTO, Worst Year in Tourism History With 1 Billion Fewer International Arrivals, 2020

-

3

Lindsey, P., Conserving Africa’s wildlife and wildlands through the COVID-19 crisis and beyond, 2020; LuxeSafaris, Safari places, Game Parks, East Africa, Accessed June 2021

-

4

UNEP, Africa yet to unleash full potential of its nature-based tourism, 2019

-

5

Reuters, Jobs gone, investments wasted: Africa’s deserted safaris leave mounting toll, June 2020

-

6

African Wildlife Foundation, Mountain gorilla tourism drives economic growth and conservation

-

7

The Ellen Fund (Ellen DeGeneres), https://theellenfund.org/

-

8

The East African, Ellen’s campus opens in Rwanda, February 2022

-

9

World Bank, Supporting Sustainable Livelihoods through Wildlife Tourism, 2018

-

10

World Bank, Supporting Sustainable Lives through Wildlife Tourism, 2018

- 11

-

12

BIOPAMA, Closing The Gap: Improving financing and resourcing of protected and conserved areas in Eastern and Southern Africa, 2018

-

13

The Nature Conservancy, Closing the Nature Funding Gap, 2020

-

14

Linking Tourism & Conservation (LT&C), Chitwan and Bardia National Park, Nepal – Stakeholder cooperations make for an effective conservation model, 2019

-

15

Linking Tourism & Conservation (LT&C), South African National Parks (SANParks) – Supported by thriving tourism activities, 2019

-

16

Linking Tourism & Conservation (LT&C), Birding supports endangered species at Delaware Bay, New Jersey, USA, 2019

-

17

The Convention on Biological Diversity, June, 2021

-

18

Sustainable Development Goals, June 2021

-

19

Technavio, Global Sustainable Tourism Market 2019-2023, 2020