Dalberg uses cookies and related technologies to improve the way the site functions. A cookie is a text file that is stored on your device. We use these text files for functionality such as to analyze our traffic or to personalize content. You can easily control how we use cookies on your device by adjusting the settings below, and you may also change those settings at any time by visiting our privacy policy page.

Small and growing businesses create close to 60% of new jobs in emerging markets, profoundly impacting livelihoods and economies. But their impact could increase significantly if the organizations and funders that support them focus their programs on five key considerations that are examined in a major report by Argidius in partnership with Dalberg.

As an important component of economic transformation in emerging markets, small and growing businesses (SGBs) create jobs, drive innovation, and deliver goods and services to address consumer needs. By definition, they are commercially viable businesses employing between five and 250 people, and have significant potential – and ambition – for growth. Many are family-run enterprises or entrepreneurial ventures.

But these small businesses often face difficulty when it comes to accessing business resources, knowledge, and finance, and in order for them to grow and reach their potential, their challenges need to be addressed.

This is where business development services (BDS) such as coaching, networking, training, and consulting play a critical role. These services are offered by hundreds of incubators, accelerators, technical assistance providers, and others around the world, and help early-stage entrepreneurs grow and secure funding. They are widely known to support growth, improve productivity, create more jobs, and ultimately drive economic transformation – but there is no one ‘recipe for success,’ and consequently, outcomes can differ.

Supporting the Vital Growth of SGBs

In the case of a sugar, spice, and condiment manufacturer in Guatemala, support was needed to create a long-term strategy as the owners were overwhelmed by the daily necessities of running the business. They applied to a BDS program offered by Bpeace, who assigned a high-value consultant to work with the business, interviewing the owners and all 24 members of their staff. This helped recognize where employee roles were misaligned with their abilities and how the business owners could better delegate tasks and trust their staff. As a result of working with the full team, the consultant was able to help the business become more efficient, and the business owners felt more confident with a strategy in place to guide their decision-making.

Another entrepreneur, concerned because sales were good but profits were not, turned to TechnoServe where the team recognized that he was underpricing his products. They helped him understand how proper pricing could improve profitability through the example of another entrepreneur who improved his margins after adjusting his pricing strategy. The team then provided training and implementation support. When data demonstrated that he was making the same number of sales at a higher margin, the entrepreneur was encouraged to maintain the new pricing strategy – a positive outcome for the business.

But outcomes differ widely among support programs, even among programs delivered by the same provider. In a 2016 evaluation of 15 programs from Village Capital, GALI, an organization that investigates program effectiveness, found that the highest performing programs generated an average of US$ 86,000 in 1-year incremental investment growth per enterprise, compared to an average of US$ 28,000 per enterprise in the lowest-performing programs.

Findings show that among high-performing programs there are fewer but more qualified and experienced applications from SGBs, entrepreneurs have more time to work on their own or with their teams, and there is a strong element of networking, peer learning, and collaboration.

The Qualities of High Performing Programs

The search to answer whether, how, and why accelerators contribute to a program’s success was the starting point for an exploration of the SGB ecosystem by Argidius, an organization that tackles poverty through enterprise development. Their 8-year journey of extensive data collection and research set out to uncover and best identify how enterprises grow and create employment.

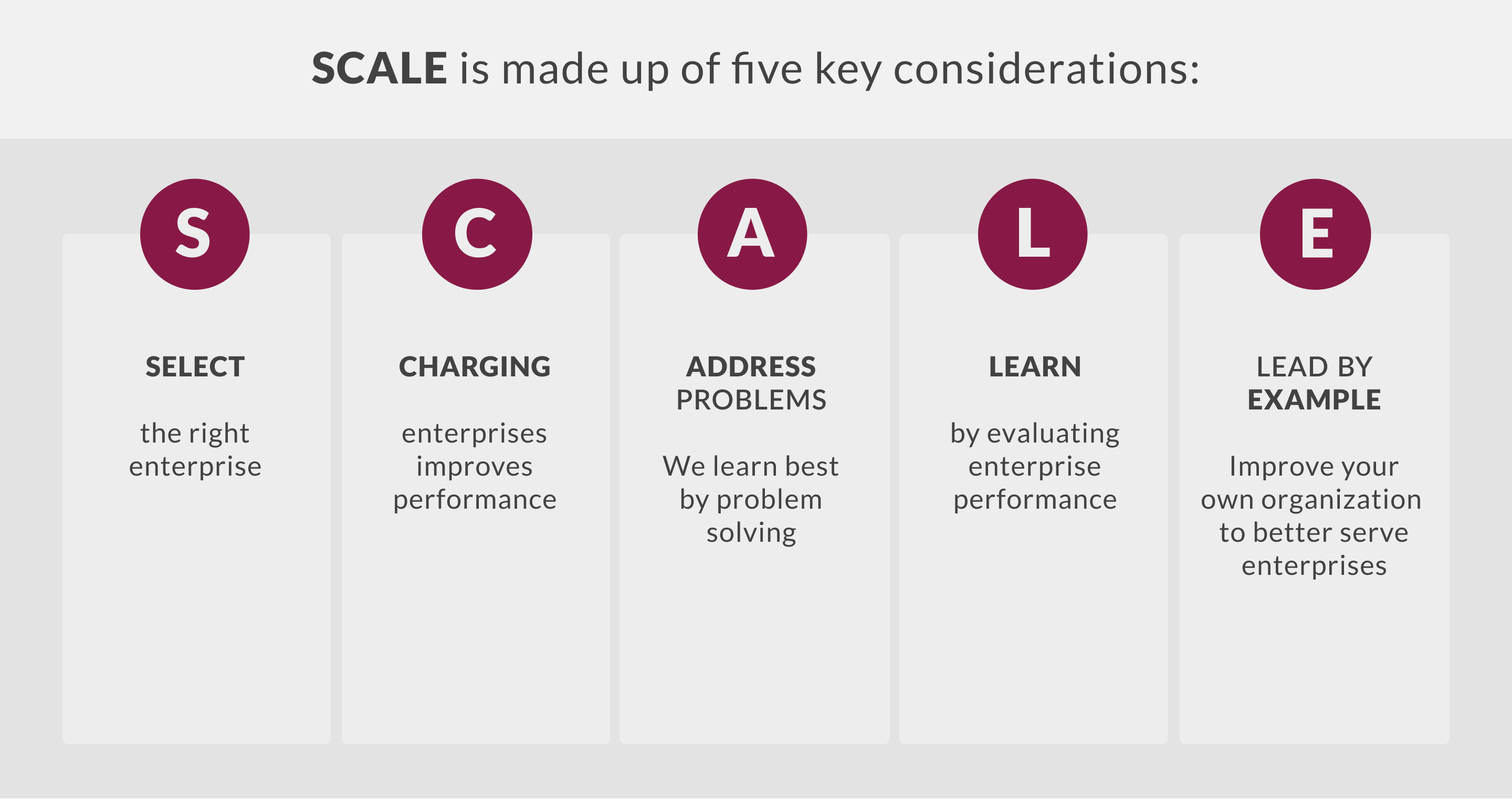

The pattern of common characteristics that emerged among high-performing support programs became SCALE, and it serves as a lens through which to look at business development programs. For BDS organizations, it can suggest ways to improve their impact. For a funder, applying the SCALE lens can help them see what good can look like and how to help grantees achieve better, more impactful results. It can also help entrepreneurs build more successful businesses, with the ultimate goal of creating the jobs that will improve lives and livelihoods.

Argidius partnered with Dalberg to distill their research and produce a major report that examines each of the considerations and the extensive evidence-base of how they contribute to successful outcomes. Dalberg also created an accompanying diagnostic toolkit to help organizations within the SGB ecosystem use SCALE as they strive for better outcomes.

A separate lens for gender and inclusion has also been applied to each of the SCALE considerations to illustrate how it works in practice, and includes a diagnostic tool that enables organizations to assess themselves through a gender and inclusion lens.

When this lens is applied to the first consideration – S (Select the right enterprise) – it can ensure that everyone enjoys an equal opportunity to take part in the process. One of the ways that BDS organizations can accomplish this is by proactively ensuring there is female representation in all cohorts, and proactively recruiting women when targeting male-dominated sectors. In addition, they can track the percentage of women employees in an enterprise, as well as women in leadership positions, and to look for enterprises that hire women, and have women in leadership roles.

BDS providers are also encouraged to ‘Learn by evaluating enterprise performance’ (the fourth consideration), identifying when some groups are performing differently and finding ways to provide more targeted support. In applying the gender and inclusion lens here, they might consider disaggregating data to determine whether women (and other minorities or vulnerable populations) are performing differently than men, or other program participants.

On average, female-led enterprises have fewer employees, weaker sales, and lower profits, with a gap as high as 82% compared with male-led enterprises.

Identifying and addressing the factors that drive this gap is critical to leveling the playing field for women. They may also consider gender education gaps when asking entrepreneurs to analyze data, especially in instances where women had limited access to school and may need additional support to learn how to analyze information.

SCALE in Action

To see how SCALE works in practice, the report includes case studies of a number of BDS providers–including Village Capital, PUM, BPeace and TechnoServe – that have integrated SCALE into their programming. Different considerations are highlighted in each case study and show the synergies between components and common approaches among organizations.

One provider, Bpeace, made two straightforward adjustments to its programs in alignment with SCALE considerations – it introduced a program fee for its clients and adjusted the timing and intensity of delivery to better address entrepreneurs’ problems. As a result of these relatively small changes, Bpeace saw a significant improvement in performance between otherwise similar cohorts. The new cohort generated US$ 3.4 M in incremental revenue and 62 full-time jobs in just one year, while a previous cohort that had received support under the original model generated US$ 180,000 in incremental revenue and 32 jobs after two years.

Furthermore, charging enterprises helped Bpeace establish a reputation for high-quality, valuable support that entrepreneurs are willing to pay for. This has attracted enterprises that may not otherwise have applied for its program. Bpeace noticed that the entrepreneurs who were charged felt more like ”real clients” and were more likely to speak up when they wanted a shift in the kind of support they were receiving. This change in attitude enabled Bpeace to better tailor its program to client needs.

Conclusion

What SCALE ultimately shows is that growth and more jobs are possible and within reach for organizations that are looking to improve program outcomes. It is a tool that can be used by every organization within the SGB ecosystem: the information, guidance, and inspiration needed to make adjustments and maximize impact on SGBs are freely available in the report.

Dalberg joins Argidius in their hope that this work will bring together practitioners and funding partners to continue the journey of developing and refining support programs that will benefit SGBs in emerging markets. The goal is to help them appropriately scale and create the formal, productive employment that is seen as one of the key pathways out of poverty into a resilient and sustainable future.

The report has already been translated into French, Portuguese, and Spanish.

Photos were provided to Argidius and Dalberg by Stuart Freedman, Sven Torfinn (Panos), James Rodriques (Panos), Thriive Nicaragua, CRS, and Village Capital.