Dalberg uses cookies and related technologies to improve the way the site functions. A cookie is a text file that is stored on your device. We use these text files for functionality such as to analyze our traffic or to personalize content. You can easily control how we use cookies on your device by adjusting the settings below, and you may also change those settings at any time by visiting our privacy policy page.

Earlier this year, Dalberg’s Americas offices brought together several leaders to discuss the LGBTQ+ movement through the lens of intersectionality. The talk covered why the intersecting experiences of oppression must be considered in evaluating both internal diversity and inclusion efforts and external interactions, which is a topic of utmost importance to us as a firm. This article draws from a robust conversation with Callen-Lorde’s Anthony Fortenberry, the National Center for Lesbian Right’s Elizabeth Lanyon, and Google Diversity Business Partner Cornell Verdeja-Woodson to show why today’s context, a historical understanding, and examples from the real world all have a role to play in understanding how to meaningfully prioritize people with multiple identities.

We are living in momentous times. The tragic murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis sparked outrage across the country and around the world, as hundreds of organizations made statements to support the urgency of the Black Lives Matter movement, and people around the world voiced their disappointment at the lack of progress on anti-racism efforts and racial equity. At the same time, the Supreme Court’s historic ruling on Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 provided millions of LGBTQ+ individuals with protection from employment discrimination and was widely considered a major step in the right direction for LGBTQ+ equality in the United States.

For many people identifying as both Black and LGBTQ+, having to simultaneously grapple with the anger of witnessing police brutality towards yet another Black person and the pride of hearing the Supreme Court ruling was a tremendous amount to process. Yet this is part of what it means to sit at the intersection of multiple identities: to experience the world through a multi-faceted lens of discrimination and disadvantage, as well as progress and pride.

In this article, we provide an overview of intersectionality, describe the value and importance for employers, and profile a cross-section of LGBTQ+ leaders to highlight how organizations may apply some of these lessons to their workplace to build a culture of equity and inclusiveness.

When intersectionality comes to work

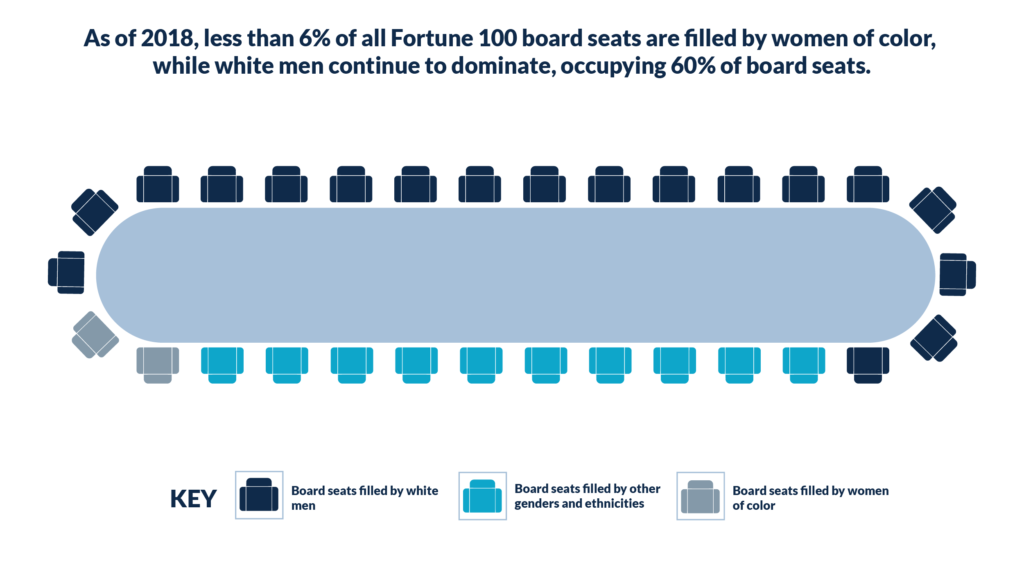

Beyond the personal realm, there is an increasing awareness of the need to recognize and design for intersectionality at work. Most organizations’ existing diversity and inclusion (D&I) initiatives do not take an intersectional lens, in that they fail to look at the ways people are affected by multiple forms of discrimination and inequity. For instance, diversity initiatives that center on “all women” often do not center on non-white women, and as a result, fail to account for the multidimensional impact of race and gender on hiring practices, promotion tracks, and more. These efforts to tackle inequality and injustice toward women therefore end up perpetuating systems of oppression—the opposite aim of most D&I efforts. [1] [2]

Some progress on D&I has been made in recent years, but data reveals that commitments to action are still lacking. As of 2018, less than 6% of all Fortune 100 board seats were filled by women of color, while white men continue to dominate, occupying 60% of board seats.[3] Additionally, fewer than 15 Fortune 100 companies have a C-suite that is comprised of one-third or more of non-white executives.[4]

Integrating intersectionality

In recent years, many organizations have sought to catalyze more inclusion by encouraging staff to “bring your whole self to work.” This is a compelling idea, but it does not clearly account for the intersectional lens required to enable individuals to truly express all aspects of their identity without fear of discrimination in the workplace.

D&I efforts have been present in many workplaces for decades, but applying intersectionality to these efforts is still a relatively recent initiative.[5] The term “intersectionality” was introduced by Kimberlé Crenshaw, a professor and leading thinker in critical race theory, in 1989 to reference the unique oppression faced by Black women, who not only experience race and gender discrimination by themselves, but also experience the combined effects of both forms of discrimination.[6] The term has since been expanded to reference how various identities, including race, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, age, and disability status, intersect to influence experiences of discrimination.

A holistic approach to achieving equality

Integrating intersectionality into organizations’ practices and attitudes is difficult but essential to the path to realizing equality for all. An intersectional lens must be applied to both internal D&I efforts and external-facing work.

Traditional internal inclusion efforts tend to categorize employees through one-dimensional aspects of their identity, whereas an intersectional approach asks organizations to look at hiring practices, workplace culture, and much more through the perspective of people who might experience discrimination on multiple fronts.[7]

Additionally, workplaces often silo D&I efforts, which is counterintuitive to creating an environment that is fully intersectional, where employees’ various identities are just as valued as their professional development or productivity. This can be seen in companies that appoint specific people to lead D&I initiatives while not making an additional effort to ensure that all employees have the opportunity to contribute to and learn about these initiatives.

Organizations that serve clients—including healthcare and counseling centers, social services, legal organizations, and advisory services—have an especially important role to play in integrating and prioritizing an intersectional lens in their external-facing work. They are at risk of falling short of addressing clients’ needs if intersectionality is not a consideration.[8]

Many systems, such as healthcare, were built to accommodate singular identities (e.g., women, Black Americans, LGBTQ+ individuals) rather than account for the unique needs of those at the intersection of multiple marginalized identities, therefore perpetuating inequality.[9] For instance, disabled women of color face not only racial barriers in accessing healthcare, but also barriers as a result of their disability status, such as when healthcare workers bypass communicating with the patient in favor of communicating directly with their carer.[10]

Three angles on creating a more inclusive work environment through intersectionality

Fostering an internal culture of intersectionality looks different for every company, and those who are embracing it today are forging a new path for the future. Here is how intersectionality influences the culture of three spotlight organizations:

- Anthony Fortenberry (Chief Nursing Officer, Callen-Lorde). Callen-Lorde is a community health center that provides sensitive, quality healthcare and related services to New York’s LGBTQ+ communities.

- Elizabeth Lanyon (Associate Director of Philanthropy, National Center for Lesbian Rights). NCLR is a non-profit, public interest law firm that advances LGBTQ+ rights through litigation, legislation, policy, and public education.

- Cornell Verdeja-Woodson (Diversity Business Partner, Google; Founder and President, Brave Trainings). Brave Trainings is a social justice consulting firm that works with organizations to increase their diversity.

1. Creating an internal culture of inclusion begins with leadership

“It really starts with the top leadership, making sure that folks know all the way down that intersectionality is a top priority. How does an organization’s top leadership reflect considerations of intersectionality in hiring practices, promotions, and performance evaluations?”

Cornell Verdeja-Woodson

It is clear that creating a workplace culture that values intersectionality is not possible without true buy-in from leadership, which is reflected in actions and policies. This can be demonstrated in multiple ways. One instance is in the diversity of senior leadership—actively diversifying senior leadership to include individuals who hold multiple marginalized identities has a significant effect on the morale and retention rate of junior minority employees, who may not often see themselves represented at higher levels. In doing this, it is important to avoid focusing diversity efforts on singular dimensions of identity, such as including only more white women or Black men.[11]

Another instance is through leading by example. The organization benefits when senior leaders express willingness to question policies that may not consider intersectionality, or when senior team members actively encourage open, difficult discussions around intersectionality, privilege, and oppression.

2. Provide consistent opportunities for education and awareness

“Encourage a culture of critical love and organic education. Organizations should commit to ongoing training and support through creating safe spaces for informed conversations.”

Anthony Fortenberry

Building a workplace that prioritizes intersectionality requires ongoing education and awareness. While one-time trainings on microaggressions, implicit bias, privilege, and similar topics are important and necessary, they will not be effective without more consistent “organic education.” Creating an environment where organic education can thrive requires that employees acknowledge the relevance of feedback from others on discriminatory behavior and that employees feel comfortable including such topics into everyday conversations without risk of repercussions or judgment.

3. Complement education with internal policy change

Developing fully inclusive policies is a necessary next step in creating an intersectional workplace. Organizations may find it useful to integrate intersectionality directly into their mission and values statements. Strengthening anti-discrimination, transparency, and reporting policies is also critical—in particular, a commitment to collecting data that includes intersectional identities is a straightforward method for organizations to track their progress.[12]

Furthermore, recognizing the unique needs of individuals with various intersecting identities will often mean revisiting existing company policies to identify policies that presume identities are monolithic or favor those who have one marginalized identity over those who have many.

Policies may need to be expanded to accommodate an intersectional lens, such as providing lactation rooms for all nursing individuals, modifying terminology to be more inclusive of the full LGBTQ+ spectrum, and providing flexibility in work schedules for all employees, not just those who are traditionally seen as primary caregivers.[13] Conducting regular internal policy audits may ensure that these policies stay up-to-date and properly address the needs of all employees.

Intersectionality in action: Real-world stories

The three spotlight organizations also revealed several key insights on how an intersectional lens informs the external-facing work of various types of organizations and how organizations can be more proactive in fostering an internal culture of intersectionality within their own workplaces.

1. Health sector spotlight: Callen-Lorde Community Health Center

“At Callen-Lorde, we are very invested in addressing healthcare disparities and inequities for marginalized populations, such as LGBTQ+ people of color, and especially trans people of color. We recognize that racial inequities are a core determinant of individuals’ access to safe, high-quality healthcare services. Understanding the impact of intersectional identities on people’s ability to live healthy, happy lives also impacts our ability to provide better healthcare services to the community.”

Anthony Fortenberry

In the health sector, taking an intersectional lens to care is a promising way of recognizing and understanding the social determinants of health disparities and inequities. Research in the past decade has revealed that environmental and social factors, such as race, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and location, result in significant disparities in the quality of healthcare.

At Callen-Lorde, recognizing these intersectional disparities allows health workers to tailor care to fit the unique needs of each patient. Approaching care with an intersectional lens is crucial to the health outcomes they help to create.

For instance, it cannot be assumed that an uninsured Black woman will respond to a health check-up in the same way as an insured white man, as the former patient has likely dealt with years, if not decades, of practitioners doubting her symptoms and limiting treatments as a result of her identity.[14] To provide equitable healthcare and promote the well-being of all, care at Callen-Lorde is contextualized in the lived experiences of marginalized communities.

2. Social sector spotlight: National Center for Lesbian Rights (NCLR)

“Our services are primarily in support of LGBTQ+ people and their families. Our work wouldn’t be what it is without understanding intersections of race, gender, and sexuality. We address the whole person and recognize the identities that we all embody. In that way, intersectionality has always been baked into our mission at NCLR—we strongly recognize the importance of honoring our whole selves in our work. NCLR understands that the liberation of LGBTQ+ people is deeply tied to the liberation of all people, and our commitment to anti-racism is central to our mission of equality and justice.”

Elizabeth Lanyon

Many social sector organizations that advocate on behalf of specific marginalized populations (e.g., women, immigrants, low-income individuals, BIPOC, LGBTQ+ individuals, and more) are well-positioned to incorporate an intersectional lens into their work. NCLR has incorporated this lens into their mission, making it a fundamental part of both their day-to-day work and movement-building efforts.

NCLR recognizes the relevance of intersectionality in everyday practices and policies. They see intersectionality as key to progress for all—without it, social sector organizations may run the risk of improving the well-being of more privileged communities while leaving marginalized communities behind.[15]

For instance, the 2015 decision to legalize same-sex marriage in the U.S. was considered a major success for LGBTQ+ people and organizations around the country, but it soon became very apparent that the legality of same-sex marriage did not equally improve the well-being of all members of the LGBTQ+ community, especially those who also lived at intersections of other marginalized identities.[16]

NCLR’s current Executive Director, Imani Rupert-Gordon, has been a vocal advocate for recognizing the importance of intersectionality in the LGBTQ+ equality movement. While she acknowledges the victories of the movement in recent years, she also continually pushes for broader inclusivity by highlighting the layers of oppression many members of the LGBTQ+ community still face, including LGBTQ+ people of color (especially Black trans women) and low-income LGBTQ+ people. Rupert-Gordon is actively positioning NCLR to address the needs of LGBTQ+ people who are not well-represented in the larger movement and to help mold the movement to “include more of us and to protect all of us.”[17]

3. Private sector spotlights: Google and Brave Trainings, LLC

“In my work at both Google and Brave Trainings, I aim to center the unique lived experiences of individuals who live at the intersection of various layers of oppression, especially queer, trans women of color, while also recognizing that individuals can simultaneously hold oppressed and privileged identities. Organizations should look at the businesses they are working with and conduct due diligence. Do these businesses have a history of discriminatory practices? While an organization may not be able to change their clients’ policies, it will reflect on their values and dedication to intersectionality.”

Cornell Verdeja-Woodson

In external-facing work, private sector organizations should ensure that their commitment to intersectionality is reflected in both business policies and actions. This is what Verdeja-Woodson aims to help others achieve in his work at Google. In recent months, this discussion has become more prominent, as various advocacy groups have called upon companies and universities to reconsider their business partnerships with law enforcement as a result of increased awareness around police brutality.

Google’s Diversity Business Partners, including Verdeja-Woodson, work within the organization to implement strategies that actively consider D&I efforts. This includes incorporating an intersectional lens into external practices. To do this, private sector organizations can conduct due diligence processes to determine that clients or business partners already take or are committed to taking an intersectional lens in their own work, or actively working with organizations led by or directly supporting individuals and communities with intersecting marginalized identities.

In Google’s case, the organization has built strong long-term relationships with educational institutions, policymakers, and community organizations that target marginalized communities through their charitable arm, Google.org. This work includes philanthropic support to organizations (e.g., Impact Justice, which builds restorative justice diversion programs primarily for youth of color) and digital skills coaching for Black and Latinx small business owners, including women entrepreneurs.[18]

Additionally, Google integrates a 2,000 person team of “Inclusion Champions” throughout their product and service lines to ensure that intersectionality is a consistent consideration throughout the process of designing, developing, and marketing new products. Examples include tailoring A.I. technology to recognize how ethnicity, gender, age, and more affect the way people interact with a product and partnering with ad agencies with experience in creating intersectional marketing campaigns.[19] [20]

Final learnings

As the workforce becomes increasingly diverse, an organization’s ability to incorporate an intersectional lens into its external business and internal inclusion practices will ensure that it will remain competitive and retain top talent.[21]The value of intersectionality is clear, but for organizations to transition from intent to action, some changes to traditional ways of working and existing D&I efforts will likely be necessary. There is optimism that conversations around intersectionality will continue to be brought to the fore in coming years, and that senior leadership will continue to become increasingly diverse.[22] Developing an intersectional workplace will require ongoing effort and commitment from organizations, but if done well, there is significant potential to create an environment where individuals of all identities can thrive and truly bring their whole selves to work.

Click here to to download a PDF version of this article.

- Womankind, “Intersectionality 101: what is it and why is it important?,” 2019.

- Jennifer Kim. “Intersectionality 101: Why ‘we’re focusing on women’ doesn’t work for Diversity & Inclusion,” 2018.

- Harvard Law School Forum on Corporate Governance, “Missing Pieces Report: The 2018 Board Diversity Census of Women and Minorities on Fortune 500 Boards,” 2019.

- Stanford University Rock Center for Corporate Governance, “Diversity in the C-Suite: The Dismal State of Diversity Among Fortune 100 Senior Executives,” 2020.

- Dennissen et. al., “Rethinking Diversity Management: An Intersectional Analysis of Diversity Networks,” 2018.

- Lavaysse et. al., “Is More Always Merrier? Intersectionality as an Antecedent of Job Insecurity,” 2018.

- Dennissen et. al., “Rethinking Diversity Management: An Intersectional Analysis of Diversity Networks,” 2018.

- Luke’s Place, “What is intersectionality and how does it impact my work?,” 2017.

- Opportunity Agenda, “Ten Tips for Putting Intersectionality into Practice,” 2017.

- European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights, “Inequalities and multiple discrimination in healthcare.”

- Criterion Institute, “Investing with an LGBTQI Lens: Rethinking Gender Analysis Across Investing Fields,” 2020.

- SocialChorus, “15 Ways to Improve Diversity and Inclusion in the Workplace.”

- Bentley University, “Intersectionality in the Workplace: Broadening the Lens of Inclusion,” 2019.

- Conscious Company, “The Healthcare Sector Needs To Address Its Implicit Bias Problem,” 2019.

- Opportunity Agenda, “Ten Tips for Putting Intersectionality into Practice,” 2017.

- GLAAD, “Mississippi LGBT advocate to GLAAD: “Intersections are where work really needs to happen in the South,” 2015.

- NCLR, “A Message from our New Executive Director – Imani Rupert-Gordon,” 2019.

- Google, “Diversity.”

- Digital Trends, “Exclusive: Google reveals 2,000-person diversity and inclusion product team,” 2020.

- Google, “9 ways we’re changing habits, so we can make more inclusive marketing at Google,” 2019.

- PeopleDoc, “Prepare for the Future of Work: Increasing workforce diversity,” 2018.

- EVERFI, “5 Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Trends We Can Expect in 2020,” 2020.