Dalberg uses cookies and related technologies to improve the way the site functions. A cookie is a text file that is stored on your device. We use these text files for functionality such as to analyze our traffic or to personalize content. You can easily control how we use cookies on your device by adjusting the settings below, and you may also change those settings at any time by visiting our privacy policy page.

None Until All Are Free: LGBTQ+ Rights Through an Intersectional Lens

By Saalar Aghili

Saalar Aghili is a consultant in Dalberg’s Justice, Equity, and Economic Mobility practice, which is dedicated to building a more equitable and just society for all people in the United States.

Over 50 years ago, Black and Latinx transgender and gender non-conforming (GNC) individuals like Marsha P. Johnson and Sylvia Rivera spearheaded the American LGBTQ+ liberation movement at the Stonewall Riots. Yet, while there has been major progress in certain areas of the LGBTQ+ movement, the same Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) transgender and GNC1 communities that paved the way for Pride and LGBTQ+ rights continue to face systemic oppression and violence at an alarming rate today due to the compounding effects of transphobia, gender conformity, and systemic racism.

Understanding how these inequities are connected and build on each other within parallel systems of oppression can help orient practitioners to target resources for transgender and GNC efforts with a racial lens, promote coordination across different stakeholders in the space, and tailor the design of interventions and programs for BIPOC transgender and GNC communities.

Transgender and GNC Rights in the U.S. Today

There has been progress in advancing transgender and GNC rights through initiatives like the world’s first legally recognized Transgender District started in San Francisco, California. At the same time, the number of anti-transgender bills introduced in state legislatures since 2015 has increased by almost 516%2. Moreover, 2021 has seen a record number of anti-transgender legislation in the US — which has so far included bans on bathroom and locker room usage, youth sports participation, and access to transgender medical care. Legislative impact can spill over into other forms of oppression and injustice as institutions shape their programs and practices in accordance with these harmful laws. With anti-transgender legislation in place, transphobic and exclusionary mindsets become further normalized among individuals and communities.

When practitioners in the American social impact and development space support efforts to bring justice and equity to LGBTQ+ communities, their strategies should acknowledge and account for the myriad of ways in which transphobia — compounded by racism — manifests as a point of origination into inequities across all sectors of social impact.

This piece aims to provide mapping guidance, exploring how systems of racism and patriarchy can deepen existing inequities for BIPOC transgender and GNC individuals’ economic and housing security, health, safety, and access to justice when compared to the greater transgender community:

Homelessness

BIPOC transgender and GNC individuals in the US are particularly vulnerable to housing insecurity, with 42% of Black transgender and GNC people having experienced homelessness at some point in their lives.3

This can be due to interpersonal estrangements from family, abandonment, and neglect that pushes them out of their own home, as well as discrimination in the current social services institutions. Homeless shelters are often ill-equipped to accommodate transgender individuals, leading to an estimated 29% of all transgender respondents who sought access to a homeless shelter in 2015 report being turned away based on their gender identity, while others can be housed in a gendered space they do not identify with and experience discrimination.4 For adults seeking a home, an estimated 19% of all transgender individuals face discrimination when seeking a home and more than 11% have been evicted because of their gender identity or non-conformity.5

For BIPOC transgender people, this housing discrimination builds on the structural barriers to housing that BIPOC communities have faced for countless years, such as redlining, that leads 42% of Black transgender people to experience homelessness at some point in their lives compared to 30% of all transgender people.6 Housing insecurity that stems from both transphobic and racist barriers has been shown to have a destabilizing effect across a BIPOC transgender person’s life, from their education to their physical and mental health, employment, and more.7

Employment

Navigating various systems of oppression can make it more difficult for BIPOC transgender and GNC individuals to secure and retain employment. Black transgender people have an extremely high unemployment rate of 26%, which is double the rate of the overall transgender population, and 4x the rate of the general population.8 Long-term unemployment has rippling effects, including the dependence on employment-based health coverage, which leaves BIPOC transgender people more vulnerable to long-term health inequities, poverty, and housing insecurity.

Institutionalized discrimination and harassment in the formal economy impede economic empowerment for transgender and GNC people, forcing them to turn to informal workplaces like sex work or other criminalized work for survival. Engaging in sex work and selling drugs make up a large share of the informal work transgender individuals partake in: 19% of all transgender individuals have resorted to some type of sex work for either money, food, or a place to sleep, while 12% of them have earned income by selling drugs. Sex work and other informal work for transgender individuals is often not a choice.9 Rather, it is a last resort and a vehicle for survival that poses an ever-present risk of violence and incarceration.

Criminalized, informal work has a direct pipeline to the penal system and broader systems of incarceration in the US. Survival sex work and other criminalized work often lead transgender individuals, particularly BIPOC transgender people, into spaces of violence with police and other members of the informal economy. Indeed, BIPOC transgender people are up to two times more likely to engage in the informal economy than white transgender people and, due to racial discrimination, are more likely to routinely be harassed, profiled, abused, and arrested by police officers.10 Legislation and policies within these systems of oppression target BIPOC transgender individuals, as seen with the “Walking While Trans” ban in New York, and incarcerate them into further systems of violence and oppression.

Gender-Based Violence (GBV)

Officially known as the Loitering for the Purpose of Prostitution Law enacted in 1976, this legislation was one example of how the criminal justice system has unfairly targeted transfeminine people of color. Police were given the right to apprehend anyone they assumed to be engaging in sex work with little to no evidence.

The statute was not indicated as gender-specific, but the policing of women’s bodies on the streets for aspects of their appearance became increasingly common and made women a target of this law. The colloquial name of the law, “Walking While Trans,” reflects how common it was for transgender women, especially transgender women of color, to be targeted: of the 152 people arrested by this statute in 2018, 80% were women (share of transgender women is unknown), 49% were Black, and 42% were Latinx11. Of the transgender individuals that have been arrested by police for sex work, nearly half (44%) indicate that the police used condoms in their possession as evidence of sex work.12 While the “Walking While Trans” ban was repealed in February 2021, laws with vague guidelines give police the agency to apprehend and arrest women with no jurisprudence.13

These high rates of arrest are markers for increased gender-based violence (GBV) because when BIPOC transgender people are incarcerated from such arrests, they face alarming rates of physical and sexual assault by both prison staff and their fellow inmates. Transgender people are ten times more likely to be sexually assaulted by their fellow inmates and five times more likely to be sexually assaulted by staff compared to cis-gendered inmates.14 As a result of these and other challenges, including denials of medical care and prolonged solitary confinement, transgender individuals subject to the penal system face elevated risk of long-term negative physical and mental health outcomes.

Almost all homicides of transgender people (99%) between 2010-2016 were a result of GBV against BIPOC transfeminine people.15

Homicides against transgender people have become increasingly prevalent; the Human Rights Campaign (HRC) tracked a record number of violent fatal incidents against transgender people in 2020, most of them targeting Black and Latinx transfeminine people.16

Systems of sexism and patriarchy perpetuate gender-based violence against the transgender and GNC community, while the disproportionate share of homicides and violence affecting BIPOC trans people is rooted in the same systems of racism that have been murdering BIPOC individuals through police violence, like Tony McDade, Layleen Xtravaganza Cubilette-Polanco, Kayden Clarke, and the other countless transgender names that are left misgendered and deadnamed.

Health

Each of these experiences of homelessness, social exclusion, survival sex work, gender-based violence, and incarceration pose distinct threats to the health and wellbeing of BIPOC transgender and GNC people.

LGBTQ+ Americans face worse physical and mental health outcomes relative to the general population,17 with BIPOC and transgender communities suffering from the deepest disparities. HIV/AIDS is a particularly acute crisis in this community; BIPOC transgender people have one of the highest rates of HIV in the country – making up over 48% of new HIV diagnoses among transgender people, with over 92% of those new HIV diagnoses among transfeminine people.18 Other physical health crises, such as drug addiction and overdose, can also be connected to involvement in informal markets and criminalized spaces.

Navigating layers of systemic oppression takes a toll on mental health as well, particularly from an early age. 39% of transgender individuals reported currently experiencing serious psychological distress, a rate nearly eight times higher than in the U.S. population (5%), as many are likely to experience family estrangement and neglect while grasping with their identities at the time.19 While BIPOC transgender and GNC individuals face similar rates of mental health issues as the broader transgender and GNC community, they face greater barriers to treatment due to mistrust of the medical community, lower rates of insurance coverage, and unequal rates of mental health diagnoses.20

Similarly, gender-affirming care can be a pivotal, life-saving opportunity for BIPOC transgender people, but social determinants of health like income pose barriers to access it. Income can be a significant determinant for transgender individuals in accessing hormone therapy and extreme poverty among BIPOC transgender individuals highlights how acute this problem is.

What’s more, 15% of all transgender individuals report a household annual income of less than $10,000, in which the rate more than doubles for Black transgender people (34%).21 Transgender individuals with an annual income of less than $10,000 are almost half as likely to access hormone therapy than those making more than $50,000 (37% vs 66%), resulting in many BIPOC transgender and GNC people resorting to communal crowdfunding, such as a GoFundMe page, and mutual aid collectives to fund their essential healthcare.22

Years of low-income and generational wealth inequality from enslavement and Jim Crow create barriers to self-determination for BIPOC transgender and GNC individuals, which perpetuates negative long-term health outcomes alongside poverty for these communities.

Looking Ahead

There are currently growing efforts underway by stakeholders in the LGBTQ+ space that pose future opportunities to target these resources for BIPOC transgender and GNC communities. Among gender lens investors, 7.2% of funds did report taking an LGBTQ+ lens in their work, showing the growing relevance of LGBTQ+ issues in advancing gender equity.23 Philanthropic funding specifically for the transgender community has increased from less than $4 million in 2012 to over $22 million in 2017. The focus on transgender communities, however, is only 12% of all LGBTQ+ funding with no explicit ties to race.24

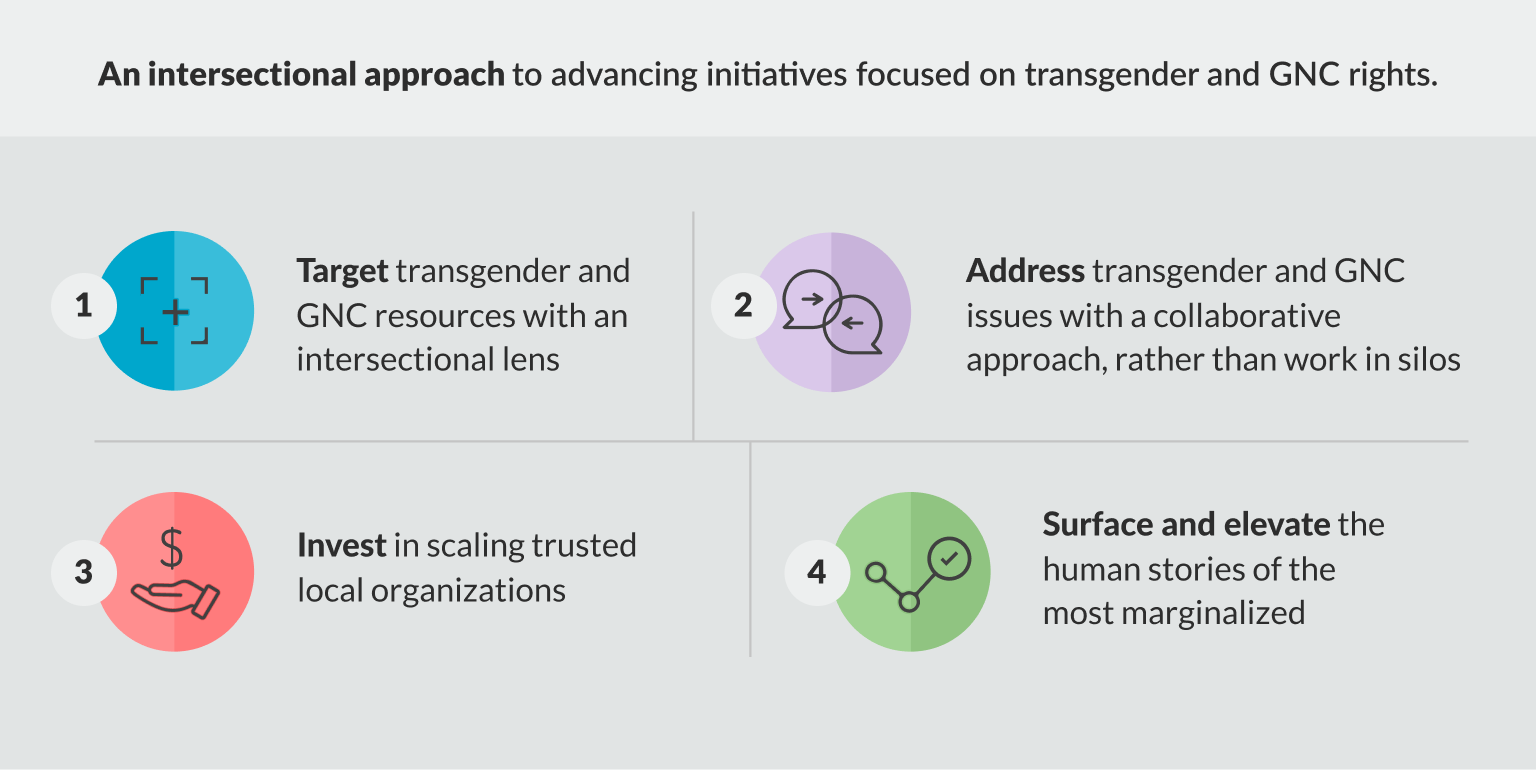

The need is clear – and the time is now to create a more intersectional approach to advancing initiatives focused on transgender and GNC rights. The following four steps are a place to start:

- Target transgender and GNC resources with an intersectional lens.

While funders and investors have increasingly taken an LGBTQ+ lens in their work and targeted more funds for transgender communities, they often lack an intersectional approach with race. There is hope on the horizon: Many of these foundations have dedicated intersectional teams that can be leveraged for LGBTQ+ specific programs to ensure support and access to BIPOC communities as well. In our work at Dalberg, we have begun to take an intersectional approach from a race and gender perspective, which has enabled us to apply gender and anti-racism toolkits across project work that may have not had an explicit tie to systemic racism or patriarchy. - Address transgender and GNC issues with a collaborative approach, rather than work in silos.

One method is for organizations focusing on one domain of LGBTQ+ issues (e.g., homelessness) to collaborate with organizations in other domains that are related or connected, such as employment. By identifying hubs of inequity, practitioners can use channels that go up or downstream and promote collaboration across practitioners in the space to work towards breaking down the pipelines that connect these inequities to one another. Another method of collaboration with organizations can be at different scales, such as local actors working with national organizations. - Invest in scaling trusted local organizations.

Much support for BIPOC transgender people resides within non-profits, community aid collectives, and direct service providers working at local levels. Many of these efforts are grassroots and already take a holistic approach in providing support that is specifically catered to BIPOC transgender and GNC people, including services that cross-cut domains of issues (e.g., housing, employment, and health) but lack the adequate funding to scale. More importantly, these local organizations have often established trust with communities that historically distrust across all domains of service providers. While there are funders on the same scale, such as faith-based funders, aligning on an ideological level may be difficult for these actors. National organizations can leverage their resources, particularly funding, to support growing local organization efforts. - Surface and elevate the human stories of the most marginalized.

When an intervention is catered for the user that is most limited or negatively impacted, it will generally be helpful for all stakeholders. Often, designs addressing LGBTQ+ issues can miss the more critical needs of BIPOC transgender and GNC people. By highlighting the needs for BIPOC transgender and GNC people, there is more potential for a depth of impact. At a minimum, LGBTQ+ research should be representative of demographics such as race, gender, socioeconomics, and geography.One approach is to take an equity-centered, participatory design approach to center the voices and experiences of the most historically marginalized communities through primary research of 1:1 interviews, small group discussions, and co-creation activities.

For example, Dalberg’s Design team elevated the voices of transgender communities in India and Indonesia to inform our insights into challenges related to the design and implementation of national digital identity systems. Even with secondary research related to LGBTQ+ issues, it can be as simple as highlighting statistics and data specific to a Black transgender woman, rather than a cis-white gay man. Centering the voices of the most marginalized can expand the perception of what LGBTQ+ means to practitioners, but also audiences.

The magnitude of disparity BIPOC transgender Americans are confronted with demands a more intersectional approach to addressing transgender and GNC rights and livelihoods. Taking a monolithic approach to addressing transgender and GNC issues can miss so much of what is specific and unique to these communities and there are several opportunities for funders, advocates, and allies to better integrate this thinking into their work to advance LGBTQ+ equality for all.

Dalberg’s Justice, Equity, and Economic Mobility (JEM) practice works with clients and partners across the social sector to build a more equitable and just society for all people in the United States. Visit the practice’s webpage for more information

-

1

We recognize that Gender Non-Conforming (GNC) people face similar barriers and inequities, but there is a gap in available data that disseminates inequities specific to GNC people.

-

2

CNN, This record-breaking year for anti-transgender legislation would affect minors the most, 2021.

-

3

U.S. Transgender Survey, Report on the Experiences of Black Respondents, 2015.

-

4

National Center for Transgender Equality, Injustice at Every Turn, 2011.

-

5

National Center for Transgender Equality, Injustice at Every Turn, 2011.

-

6

National Center for Transgender Equality, U.S. Transgender Survey, 2015.

-

7

Axios, Watch: A Conversation on Latino LGBTQ Issues, 2021.

-

8

National Center for Transgender Equality, Injustice at Every Turn, 2011.

-

9

National Center for Transgender Equality, U.S. Transgender Survey, 2015.

-

10

National Center for Transgender Equality, Injustice at Every Turn, 2011.

-

11

The Cut, Walking While Trans Law in New York Explained, 2020.

-

12

National Center for Transgender Equality, U.S. Transgender Survey, 2015.

-

13

NPR, New York Repeals ‘Walking While Trans’ Law, 2021.

-

14

National Center for Transgender Equality, Police, Jails & Prisons, 2021.

-

15

Dinno, A., Homicide Rates of Transgender Individuals in the United States: 2010–2014, 2017.

-

16

Human Rights Campaign, Fatal Violence Against the Transgender and Gender Non-Conforming Community in 2021, 2021.

-

17

Movement Advancement Project, Understanding Issues Facing LGBT Americans, 2014.

-

18

CDC, HIV and Transgender People, 2021.

-

19

National Center for Transgender Equality, U.S. Transgender Survey, 2015.

-

20

Human Rights Campaign, QTBIPOC Mental Health and Well-Being, 2021.

-

21

National LGBTQ Taskforce, New Analysis Shows Startling Levels of Discrimination Against Black Transgender People, 2021.

-

22

National Center for Transgender Equality, U.S. Transgender Survey, 2015.

-

23

Wharton Social Impact Initiative, Project Sage 3.0, 2020.

-

24

National Committee for Responsive Philanthropy, Philanthropic Investment in the Transgender Community is Not Commensurate to the Threat Transgender Women of Color Face, 2019.