Dalberg uses cookies and related technologies to improve the way the site functions. A cookie is a text file that is stored on your device. We use these text files for functionality such as to analyze our traffic or to personalize content. You can easily control how we use cookies on your device by adjusting the settings below, and you may also change those settings at any time by visiting our privacy policy page.

Originally published in The Guardian

The Zika virus, now detected in 42 countries, is only the latest in a series of diseases establishing a new normal for pandemics. Sars ravaged South China in 2003, Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (Mers) shocked the Middle East in 2012, and Ebola devastated west Africa in 2014. We have seen avian influenza emerge in new geographies alongside mosquito-borne viruses, such as Chikungunya. Over the past 50 years, more than 300 infectious pathogens have either newly developed or reemerged in places where they had never been seen before.

These trends raise questions: Why are infectious diseases occurring with such frequency? Why are pandemics the new normal? The increased rate of outbreak is typically framed as a failure of the health system. Indeed, that is a critical component. But the conditions that allow for outbreak in the first place are rooted in environmental change.

The environmental degradation of natural ecosystems has resulted in many negative outcomes, one of which is the outbreak of infectious disease. The vast majority of human infectious diseases, such as malaria, Zika, and HIV/Aids, originate in animals. When we disrupt the natural environment and habitat of animals, we are poking the beast, so to speak.

Take deforestation. Destroying the delicate balance of ecological conditions in forests increases contact between humans and potential reservoirs of disease in the animal population. Evidence shows that Ebola may have been spread to humans who came into contact with infected wildlife, enabled by widespread deforestation. The environment plays a critical role in serving as a buffer against infectious disease. A failure to recognise the value of this service that forests provide means that deforestation and infectious disease outbreaks are likely to continue at alarming rates.

Infectious disease is a systems problem that requires systems solutions. Treating only one part of the overall problem – whether by vaccination, quarantine or awareness campaigns – merely scratches the surface. Effective solutions must address the system as a whole, including changes to underlying ecosystems. The field of planetary health has emerged to better understand and solve the integrated relationship between human health and the environment. It aims to shed light on health problems induced by large-scale changes to the environment, and to highlight new ways of working to address these often intractable issues.

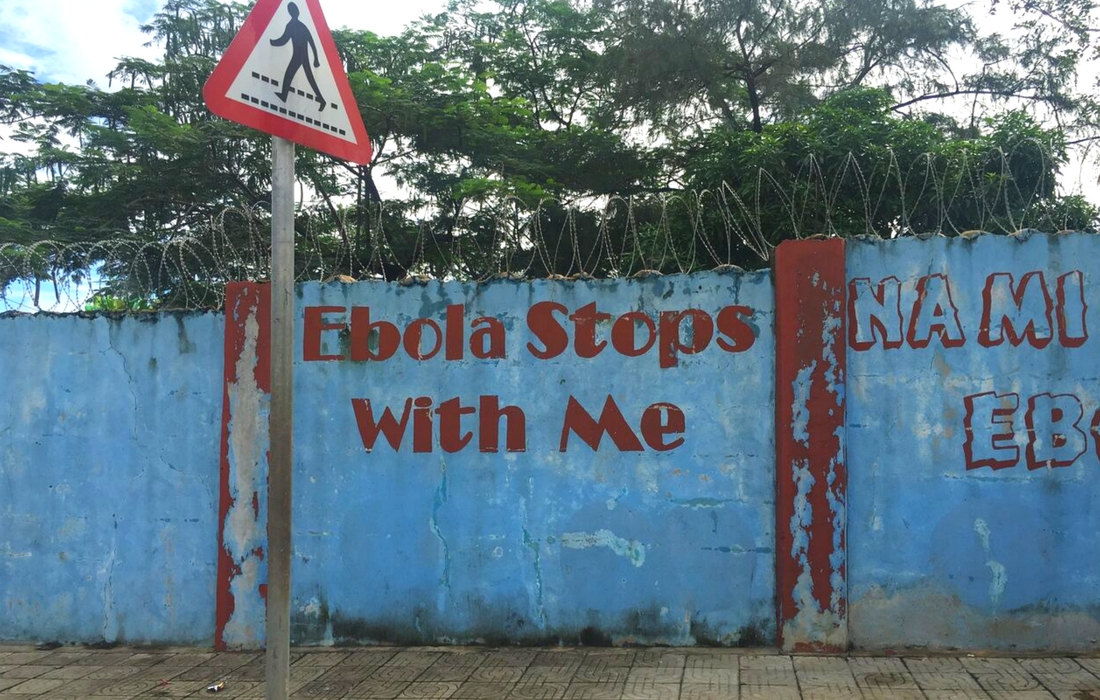

The connection between environmental change and human health is increasingly clear, but this big-picture view is not how we currently orient ourselves. Take existing public health solutions to Ebola, for example, which are to treat the disease, contain its spread, and prevent it by developing a vaccine. These are all necessary, but they miss a large set of tools found further upstream.

A way to access these tools might be to ask ourselves: can we prevent transmission of the Ebola virus from animals to humans to begin with? With planetary health, we have an opportunity to redefine prevention to include upstream solutions that safeguard the environment. For Ebola, this would mean that forest protection efforts would be added to the arsenal of tools we use to fight the disease. These solutions can have multiple benefits to the environment and to human health; for example, in addition to preventing pandemics, reducing deforestation can combat climate change, protect biodiversity, and preserve watersheds that provide clean water to nearby communities.

Planetary health draws attention to the cross-sector innovation that is needed to tackle complex problems such as infectious disease, using integrated surveillance tools incorporating both environmental and health data. For example, USAID and the Wildlife Conservation Society are creating a surveillance system, Predict, to detect and prevent spillover of potentially pandemic pathogens that can move between wildlife and people – and inform environmental and health policy to prevent it. Another example of cross-sector innovation is the Norway-Liberia agreement; Norway will give Liberia up to $150m (£104m) over the next six years to fund protective measures to squash illegal logging in its agricultural sector, with the aim of averting a future Ebola crisis.

A growing community of practice is forming around planetary health. The US-based Rockefeller Foundation and UK-based Wellcome Trust are shaping and nurturing this emerging field. They are funding research to better understand complex human-environmental systems and the range of responses that local communities, governments and international bodies can bring to bear.

Together with leading scientists, including those at the Harvard School of Public Health, the Wildlife Conservation Society, and the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, Rockefeller and Wellcome are looking into a host of issues for which a planetary health approach might be useful. These include the relationship between climate change and human nutrition, and the links between coastal ecosystems and resilience to natural disasters, among others.

“Public health alone can take us only so far in addressing today’s complex health challenges,” said Michael Myers, managing director of the Rockefeller Foundation. “We see the need for a new interdisciplinary field that’s as relevant for this century as public health was for the last – planetary health, or what we consider public health 2.0. By embracing the new reality that our health and the planet’s health are inextricably linked, the field of planetary health will identify more effective approaches to ensuring our own health.”

We don’t know what pandemics are coming in the future. What we do know is that with continued environmental degradation, outbreaks will occur with greater frequency, and the toolkit we are using to control them is incomplete. Planetary health can help us expand the toolkit by finding ways to prevent outbreaks occurring in the first place, allowing us to proactively manage the health of the human population, rather than reactively try to control deadly diseases that we don’t fully understand.

In recent years we’ve become more sophisticated at understanding and assessing nature’s value to people; from food and fuel production, to water purification and spiritual renewal, natural ecosystems provide countless services that sustain us. Protection against infectious disease is another critical service. It is time to build a field that fully recognises the important role that the environment plays in our collective health. The survival of our planet and our species depends on it.