Dalberg uses cookies and related technologies to improve the way the site functions. A cookie is a text file that is stored on your device. We use these text files for functionality such as to analyze our traffic or to personalize content. You can easily control how we use cookies on your device by adjusting the settings below, and you may also change those settings at any time by visiting our privacy policy page.

In the U.S., there are 43 million adults–nearly one in five – who read below a third-grade level, and over half of all adults read below a sixth-grade level. Low literacy is pervasive and entrenched, and those who experience it generally have poorer health, significantly lower incomes and prospects — and their children are more likely to face the same future. A new, comprehensive plan brings together stakeholders at a time that is ripe for scaling solutions around adult education — and offers future hope.

For Dan, the eldest of eight children, responsibilities in his dad’s car repair workshop took priority over his schoolwork from the third grade. His mother could not read and his father had limited reading skills, and Dan excelled at the technical work of fixing vehicles, so his reading and writing skills never progressed. Later on, he married Carla, and they moved from Mississippi to Nebraska, together starting a successful car wash business where Carla handled the administration and Dan managed the day-to-day work of the 10-person team.

Dan’s struggles with reading presented challenges even as his business grew – he memorized the flow of invoices and could respond to basic phone texts, but passed all HR and legal documents to Carla to manage. The strain intensified when they were both in their 50s. Carla was involved in a car accident and lost most of her mental processing ability over a 6-month period. Dan was unable to decipher the hospital consent forms and medication details, and struggled to communicate with the insurance agency. With Carla ill, the business lost half of its revenue, and three long-term employees were laid off. Rebuilding at this stage of life seemed like an insurmountable challenge – not to mention the job losses experienced by his team members and Carla’s ongoing care needs.

43 million adults in the U.S. — nearly one in five — read below a third-grade level, and half of all American adults read below a sixth-grade level.

Millions of people experience similar outcomes to Dan, finding it difficult or impossible to fill out a job application, take a driving test, understand a news article, cast a ballot, or help their children with schoolwork. Poor literacy skills can be a lifelong disability in areas that include understanding and responding appropriately to written texts, using numerical and mathematical concepts, and accessing, interpreting, and analyzing digital information.

The range of adults affected is as broad as the reasons are behind it, from learning differences — sometimes undiagnosed — and behavioral challenges, to language barriers, and poor socio-economic or living circumstances. Over time, people in this position, and their families, risk falling further behind as more jobs demand solid literacy skills and the income gap between skilled and unskilled workers widens even further.

A Pervasive Global Challenge

Low literacy among adults is an ongoing issue that occurs all over the world. The Program for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies (PIAAC) provides an international context for U.S. performance,1 and finds that while U.S. adults score higher in literacy than the PIAAC international average across participating countries, they score lower in both numeracy and digital problem-solving. Such comparisons to the international average paint a mixed picture of U.S. skills, but compared to higher-performing countries like Japan and Finland, the U.S. lags noticeably behind in all three domains.

Like the U.S., many countries have not seen significant improvement in literacy levels over the past 30 years or more. Some describe it as a ‘silent crisis’ because most people are unaware of the extent or detrimental effects of poor literacy, and many of those with poor literacy do not even identify as such. On top of that, it is surrounded by a pervasive sense of shame and secrecy, as well as fears of being stigmatized or denied opportunities. As a result, one of the most important aspects of supporting people with low levels of literacy is to increase their self-esteem and persuade them of the benefits of improving their reading and writing.

In the U.S,. a key problem is not that adults with poor literacy skills lack intelligence, capability, or motivation, but that too few—only 10%—receive help for their learning needs. The subject has limited visibility in the U.S. and funding from governments, the private sector, foundations and donors is hopelessly inadequate to address the size and scope of the challenge. Furthermore, the body of knowledge on adult low literacy remains sparse, lacking the high-quality datasets needed for research that can be translated into cost-effective, replicable solutions. Without strategic action, the situation will only get worse.

The Urgent Need to Invest in Adult Learning Needs

The National Action Plan for Adult Literacy takes steps towards untangling the complex web surrounding adult low literacy and aims to drive inclusive, collective action among stakeholders. The plan offers a cohesive, coordinating framework to attract funding, generate systems change, and create meaningful, lasting results at scale for one of the most urgent issues of our time. It is spearheaded by the Barbara Bush Foundation for Family Literacy which is working in partnership with Dalberg.

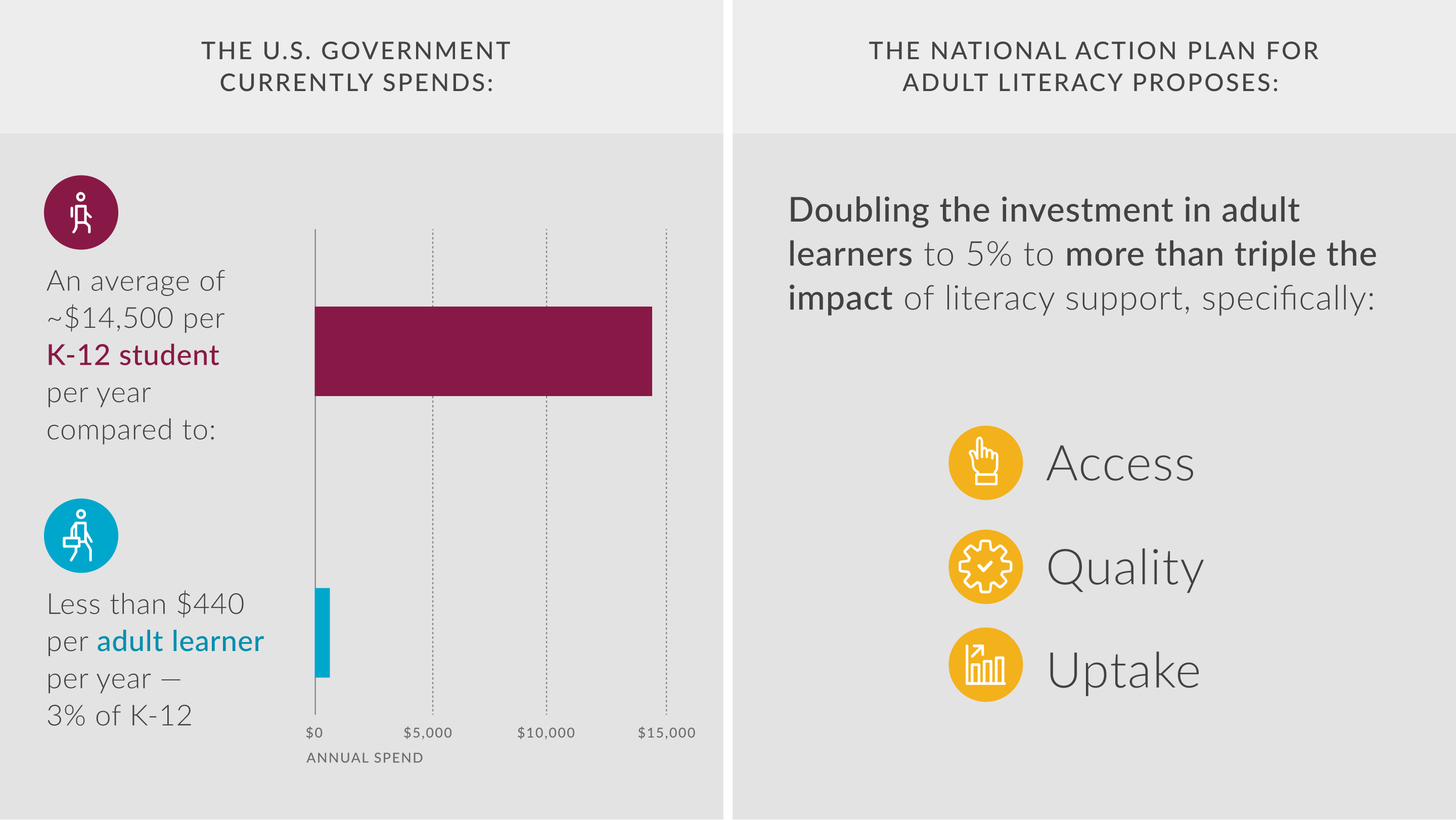

What Dalberg estimates is that governments spend under $440 per adult learner per year, less than 3% of what is spent on K-12 students, which averages about $14,500 per K-12 student per year. Working closely with the foundation, Dalberg laid out an initial goal that would see investment in adult learners doubled to 5%, which is expected to more than triple benefits in the three priority areas of access, quality and uptake of literacy support. The plan provides details of a five-pronged approach that will help achieve this, and advance change.

The Impact of Poor Literacy Skills

Low literacy takes a tremendous toll on the economy and on individuals, families, and communities, reducing income, health, and civic engagement. Adults with poor literacy skills are more likely to be unemployed or in low-paid jobs where their average annual income is $35,000—close to half of what workers with only slightly higher levels of literacy earn. About two-thirds of them earn less than $16,000 per year, and a third of those with the poorest literacy skills are unemployed.

There is also a link between poor reading and writing skills and shorter life expectancy, depression and obesity — and poor health generally.

Adults with low literacy are five times more likely to report being in poor health than adults with better reading and writing skills, and also experience higher rates of hospitalization and more frequent use of emergency room facilities. ProLiteracy Worldwide, an international nonprofit organization that supports literacy programs that help adults learn to read and write, estimates that up to $238 billion in health care costs per year are linked to low literacy.

Entire families can get caught up in the spiral of low literacy, with studies showing that children of parents with poor reading and writing skills have a 72% chance of being at the lowest level of literacy themselves in adulthood. The single most important determinant of a child’s future academic achievement is their mother’s level of education, and among children under six years of age whose parents did not complete high school, 88% live in poverty. In this way, the cycle of poverty and inequality is perpetuated in the U.S., affecting generation after generation.

As it stands currently, more people are incarcerated in the U.S. than in any other country in the world, with over two million Americans in state and federal prisons. A staggering 70% among them are classified as having low literacy skills, indicating a strong association between low literacy and higher rates of incarceration. Those without a high school diploma fare the worst and are more than twice as likely — 63% — to be incarcerated than college graduates.

Low literacy, therefore, comes at a hefty price.

For state and federal governments approximately $81 billion2 is spent each year on mass incarceration alone, according to the Bureau of Justice Statistics—and that figure might be an underestimate. In 2017, the Prison Policy Initiative estimated the actual cost on state and federal governments and impacted families is roughly $182 billion.

There is little doubt that improving reading and writing skills at scale could help break entrenched patterns, potentially saving millions if more is invested in adult learning. According to a Gallup study commissioned by the Barbara Bush Foundation, the U.S. economy could generate an estimated $2.2 trillion more per year if all adults read at or above a sixth-grade level. The benefit to society at large would be huge in terms of higher productivity, savings, and most importantly, quality of life for individuals and families.

The Opportunity for a New Chapter

There has never been a better time than now to drive meaningful, systems-level impact. With recent developments in digital technology, the capacity to reach and teach adults with literacy challenges has never been more promising—one of the few upsides of the damaging pandemic. Furthermore, American businesses of every size, across every industry, and in every state are struggling to fill open positions with even minimally qualified workers.

At this time of opportunity, Dalberg believes that the National Action Plan for Adult Literacy has the potential to redefine how American society supports not just adult literacy but adult education in general, thereby improving the lives of individuals, families, and communities living in vulnerable circumstances – and action is urgent.

To learn more about the complex issue of low adult literacy in the U.S. and the proposed plan to address it nationally, click here.