Dalberg uses cookies and related technologies to improve the way the site functions. A cookie is a text file that is stored on your device. We use these text files for functionality such as to analyze our traffic or to personalize content. You can easily control how we use cookies on your device by adjusting the settings below, and you may also change those settings at any time by visiting our privacy policy page.

Ocean fisheries are one of our most important and resilient resources, yet they are in crisis. Nearly 40% of fisheries have collapsed or are overexploited, risking the livelihoods 350 million people, the food security nearly of 3 billion people, and threatening countless species in the world’s most bio-diverse waters.

MEET PAK SONI, 36, INDONESIAN CRAB FISHERMAN.

Pak Soni is a partner on a Blue Swimming Crab (BSC) trapping boat in Indonesia. He makes a third of a boat owner’s take-home pay, which can sometimes be as many as five time more than what a boat hand makes. This amount is barely able to help him subsist or save to buy his own boat and gear.

“We use the income from shrimp to cover daily expenses, blue swimming crab to pay for big investments and boat repair, and baitfish to pay for our children’s education. Using this system, we’ve managed to avoid taking on debt.” – Pak Nur, Demak, Indonesia

To understand Pak Soni’s world, we visualized his fishing ecosystem and explored the stakeholder relationships he must navigate. The path to more sustainable fishing behavior is shaped, by the social and economic context of the “fishing group.” When this fishing community is empowered — with healthy families, strong governance, negotiation power in the market, and a network of collaborators, they can build stewardship for the ocean and take on more risks for growth.

Pak Soni’s behavior within this ecosystem is driven by factors at three levels:

Individual needs: Motivations and challenges that shape the behavior of different types of small scale fishers at different stages in their lives.

Group formation: Social and economic factors which influence collective action and strengthen the role of fishing groups in supporting sustainable practices.

Level of exploitation: Stages in marine ecosystem health that shape group and individual behavior based on short versus long term interests.

CHALLENGE #1

SMALL-SCALE FISHER COOPERATIVES UNDERCUT EACH OTHER, CANNABLIZE SALES AND DEPRESS PRICES. THEY ARE UNABLE TO OPERATIONALIZE AND STANDARDIZE THE QUALITY OF THEIR PRODUCTION TO GAIN ACCESS TO BIGGER AND BETTER MARKETS.

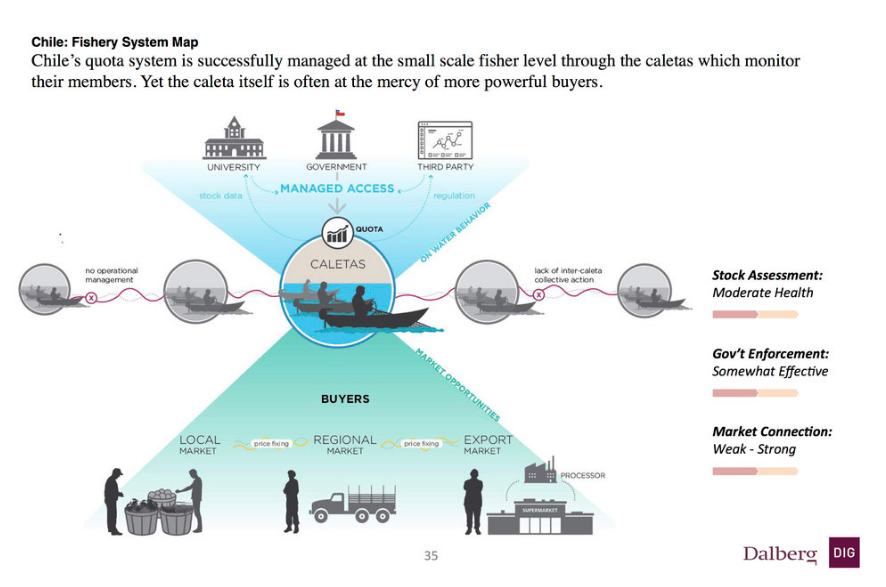

We set our prices by calling our buyers before we go out on the water. If they don’t want to buy, we don’t go out until they give us our price. – Eladio, Head of Commission Management of Chile

PROPOSED APPROACH

Fisher Knowledge-Sharing Platform Pilot: A regional group exchange platform created from the understanding that fishers take pride in their method of extraction and the level of quality of their product and would be willing to share these skills with fellow fishers. This concept was tested with a group of caletas (coops) in Chole. It allows fisher caletas to post, exchange, and rate products to strengthen collective group power and produce higher value to individual fishers. Participants can share new skills that increase income, diversify livelihoods and mitigate risk, and assist fishers to connect directly to buyers willing to pay sustainable practices and high quality catch.

KEY FEATURES

Caleta exchange platform: Design of a platform for caletas to set their desired price and volume for their products, and for buyers to post their needed products, listing their desired quantity and quality. Buyers compete to purchase the highest quality product by offering higher prices.

Quality control mechanisms: Fishers install traceability technology on their boats to verify handling, source of product, and hygiene. Buyers can then view the caleta’s profile on the Exchange Platform, to verify product quality, as well a historical performance.

Caleta matching service: For an added fee, caletas can enroll in a caleta matching service, where the platform operators suggest quality improvements that past caletas have made that have increased the value of their product, and directly connect the production managers from each caleta for better knowledge exchange.

CHALLENGE #2

SMALL-SCALE FISHERS, MIDDLEMEN AND MINI-PLANTS ALL HAVE AN “EVERYMAN FOR HIMSELF MENTALITY” THAT ERODES TRUST, FRAGMENTS RELATIONSHIPS AND EXACERBATES UNCERTAINTY.

Everyone manipulates the scales, even me. If feels wrong in terms of my relationship with my creator, but what can i do? This is what we have to do to survive. – Mas Mujid, middleman and mini-pant owner

PROPOSED APPROACH

Fisher Group Healthcare Fund: Fishers do not see the the potential of collective action to transform both their lives and improve the health of the fishery. To address this issue, we designed a healthcare fund for fisher groups in Indonesia which would enable fishers to access lower-cost health care for their families, while driving membership and loyalty to the group, which build up trust and collective bargaining power in the long term.

KEY FEATURES

Leverage state subsidies: The fishers group works with local government to connect its members to state subsidies for healthcare.

Group discounting: The fishers group aggregates its members to capture a group discount on health insurance.

CHALLENGE #3

SMALL-SCALE FISHERS’ WIDESPREAD ADOPTION OF SUSTAINABLE FISHING PRACTICES IS CHALLENGE BY MISALIGNED INCENTIVES AND POOR INFORMATION ON FISHING STOCK.

He knows better than to trawl, I scold and make fun of him all the time, telling him he’s stealing all the fish and ruining it for everyone. But what does that achieve? It’s really the government’s job, not mine. I’m just a fisher. – Pak Ansari, Fisher, Demak Indonesia

PROPOSED APPROACH

Fisher-Powered Data Collection Program Pilot: We partnered with a provider of a passive GPS tracking technology to design a data collection system that enables fisher collectives and governments to monitor data and build cost-effective strategies for sustainable fishing practices in Indonesia. Fishers deposit money for the device but then “earn out” ownership through continuous data generation.

KEY FEATURES

Enrollment & onboarding strategy: Fishers register for the program with their local collective, qualifying to purchase subsidized GPS devices. The program includes an “earn out” feature where fishers pay for a portion of the device upfront and earn out full ownership through continued data collection. The device allows them to better track their own fishing patterns as well providing peace of mind in emergency situations.

Mobilization & training: The technological provider installs the passive GPS trackers on fishers’ boats and explains the benefits of the data such as fisher locations, gear and fuel use, and time spent on the water. The GPS verifies gear type use and respect for marine closure areas, which enables fisher to capture subsidies, if available, related to sustainable fishing practices.

Data generation & use: The technological provider manages the data and generates fisher report cards for individual fishers, which are then distributed through the local fishers group. The report cards link fishing costs to seasonality, weather, and on-the-water practices, helping fishers improve efficiency and understand the connection between sustainable practices and improved stock health. Generated maps can also show the fisher’s last known location in case he becomes lost.

KEY FEATURES

Practice Verification: Third party audit confirms that fishing group fulfills requirements for seafood label, through the ‘Fisher-powered Data Collection Program’ or similar systems

Label & Market: Participating buyers brand seafood with label and market the brand with other buyers and retailers as well as directly to consumers

Return Premiums: Participating buyers return a portion of the profits to fishing communities to support projects, such as the ‘Fisher Knowledge Sharing Platform’