Dalberg uses cookies and related technologies to improve the way the site functions. A cookie is a text file that is stored on your device. We use these text files for functionality such as to analyze our traffic or to personalize content. You can easily control how we use cookies on your device by adjusting the settings below, and you may also change those settings at any time by visiting our privacy policy page.

The year 2017 witnessed multiple changes and fresh new challenges for the global health community. The WHO and the Global Fund elected new leadership at their helm, several promising public and private initiatives were launched, at a time where traditional donor funding is shrinking mainly due to anticipated U.S. government budget cuts to global health programs. Despite the prevailing context of uncertainty, we at Dalberg have selected two global health areas, old and new, that warrant a closer look: global health security and city-level focus to improve population health. We expect these two areas to grow in influence and attract more resources to become defining issues of the global health agenda going forward.

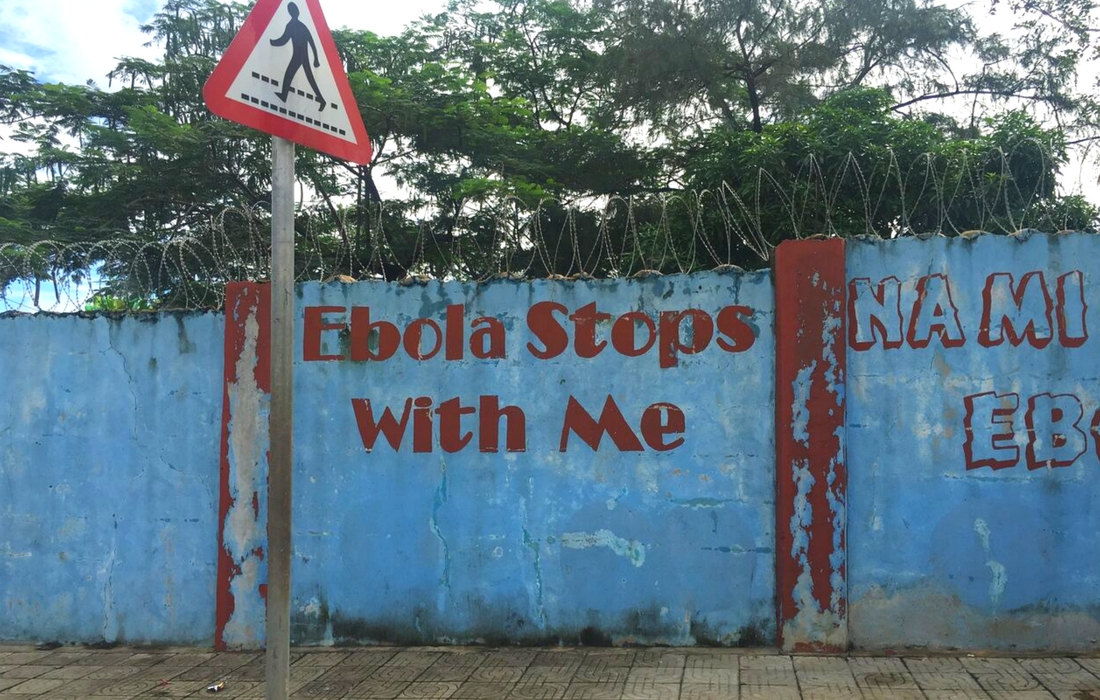

The year 2018 marks the centennial of the Spanish Flu pandemic of 1918, which claimed the lives of up to 100 million people worldwide. This milestone will provide the backdrop for discussions on the readiness of our public health emergency management systems, with a focus on learnings from the recent Ebola and Zika outbreaks.

Multiple initiatives have been launched to make the world safer from disease outbreaks, with the notable launch of the Africa Centre for Disease Control and Prevention in March 2017. The Africa CDC, headquartered in Addis Ababa, will strengthen the continent’s preparation for, and response to, outbreaks through its five regional centers in Egypt, Nigeria, Gabon, Zambia, and Kenya, working in close collaboration with national public health institutes.

At the national level, the trend for the planning and implementation of Public Health Emergency Operations Centers will likely continue thanks to WHO AFRO support. On the international stage, DFID will launch its official on-the-ground response in the wake of the Ebola crisis – its five-year Tackling Deadly Diseases in Africa Programme.

These large-scale partnerships and interventions are essential, but two system-level changes are still needed at the local level to minimize the impact of future outbreaks.

- During the preparation phase, Ministries of Health and Finance need to closely collaborate. A growing body of evidence highlights the disproportionate costs posed by a lack of coordinated response in pandemic outbreaks; however, joint planning activities among health and finance ministries are still lagging. As a result, emergency preparedness and response activities remain critically underfunded. Real efforts are now being made on this front with the first-ever Simulation Exercise on Pandemic Preparedness held for Ministers of Finance during the World Bank/IMF Annual Meetings. This exercise highlighted the need for domestic investments to contain outbreaks, the costs of a delayed response and the need for close coordination across government ministries.

- Designing a regional response model should be the next priority of public health emergency planning. The 2014 Ebola epidemic shed a light on the need for countries to develop national strategic plans to prepare for, and respond to, public health emergencies. National plans are a necessary first step, but they need to be reinforced with regional plans. The latter can strengthen the relationship between the central and regional levels of the Ministry of Health, ensuring that regional and district-level facilities are empowered to make decisions and reduce reaction time to emergent threats. We recently worked alongside the Ministries of Health in Senegal, Mali, Cameroon and Nigeria, with support from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, to develop decentralization strategies and operationalisation plans of their respective Emergency Operations Center. Recognizing that the need for preparedness is greatest along porous borders, or between countries that have extensive travel and trade relations, or pre-empting the influx of refugees from neighbouring countries, decentralization strategies pave the way to establishing strong emergency management leadership at the regional level. Decentralization also represents an opportunity to assess regional capacities, constraints, and needs, and to allocate resources in direct relation to the risks posed by each region.

Shifting leadership from national to city-level to improve population health

Today, over 55% of the world’s population lives in cities, with urban populations expected to continue growing, particularly in Asia and Africa. These demographic trends are elevating cities as the driving force for healthcare.

Beyond demographic trends, there is a growing awareness of how improved health outcomes can boost economic productivity and social cohesion. This is particularly relevant in the developing world, where rapid and unplanned urban growth is often synonymous with slums and informal settlements.

Recognizing the unique role that cities can play in fighting diseases and injuries, multiple initiatives are addressing the new urban agenda, most notably Bloomberg Philanthropies’ Partnership for Healthy Cities, Novartis Foundation’s Better Hearts Better Cities, and citiesRISE, a Global Development Incubator spin-off.

For the shift to urban healthcare to take hold, two areas must be addressed:

- Cities must engage the private sector to increase health financing. Owing to their higher economic potential, cities have the power to engage the private sector and seek financial and operational support for health infrastructure and service delivery. Our work with the Union for International Cancer Control on the C/Can 2025: City Cancer Challenge-Financing Sustainable City Cancer Treatment Infrastructure report explores ways that city leaders can crowd in new sources of finance for health infrastructure, like cancer treatment centers. Ranging from one-off to on-going investments, cities can use a range of financial tools to mix capital from public, private, and philanthropic sources to strengthen their capacity to deliver health services. Cities have a range of options available to them, everything from a municipal bond for health that could leverage private sector investors, to direct private sector debt or equity investment in health infrastructure.

- Cities, NGOs and international agencies need to prioritize local health strategies and cross-sector partnerships. The shift in burden of care from communicable to non-communicable diseases is particularly relevant in urban settings due in no small part to sedentary lifestyles and air pollution. City leaders need to rethink their approach to public health planning and build cross-sector partnerships with the urban, transport and technology sectors to develop local strategies aimed at improving urban health. This change in approach would also encourage data collection and analyses at the city level to reveal differences in mortality and morbidity trends thus allowing decision makers to adjust their urban health priorities accordingly. Cross-sectoral partnerships will also open up the possibility of using big datasets to analyze the links between urban lifestyles, the built environment, and health outcomes, potentially creating new ways to reduce disease burden through “smarter” and indirect health interventions.

Public health emergency management and increased leadership at the city level to improve population health will continue to gain momentum in the global health arena as new political realities emerge and migration patterns continue. However, there must be increased financing and greater attention on localization – the refocusing of global or national strategy to meet local needs and empower local decision makers – to realize the potential in these two fields.