Dalberg uses cookies and related technologies to improve the way the site functions. A cookie is a text file that is stored on your device. We use these text files for functionality such as to analyze our traffic or to personalize content. You can easily control how we use cookies on your device by adjusting the settings below, and you may also change those settings at any time by visiting our privacy policy page.

Expecting mothers struggle with access to quality information and care for their newborns. This contributes to a high number of infant deaths worldwide – as many as 2.8 million in 2013 – within the first 28 days of life.

Informing women of how to care for their newborn properly – for example, proper care to prevent umbilical cord infections which account for ~13% of neonatal deaths – is crucial to infants’ survival. Expectant mothers from peri-urban and rural areas often have minimal access to health facilities and antenatal clinics. Even in cases where such facilities are accessible the behavior of these women during pregnancy is influenced greatly by where they live, their families, their education and traditional socio-cultural beliefs; for example roughly two thirds of Nigerian pregnant women birth at home, either with the assistance of traditional birth attendants (TBAs) or caregivers drawn from their families and friends.

MEET UWEM, 30, NIGERIA.

Uwem has been married for 12 years and is pregnant with her fourth child. Her husband works in the city as a laborer and visits one or two times per month. She sells produce from her small farm at the local market to supplement their income. One of her friends is greatly respected for giving birth to 3 children with no assistance. She prefers going to a TBA (traditional birth attendant), or relying on friends and family for delivery and childcare advice.

“I don’t need much help now as it’s my fourth child.” – Uwem, Nigeria

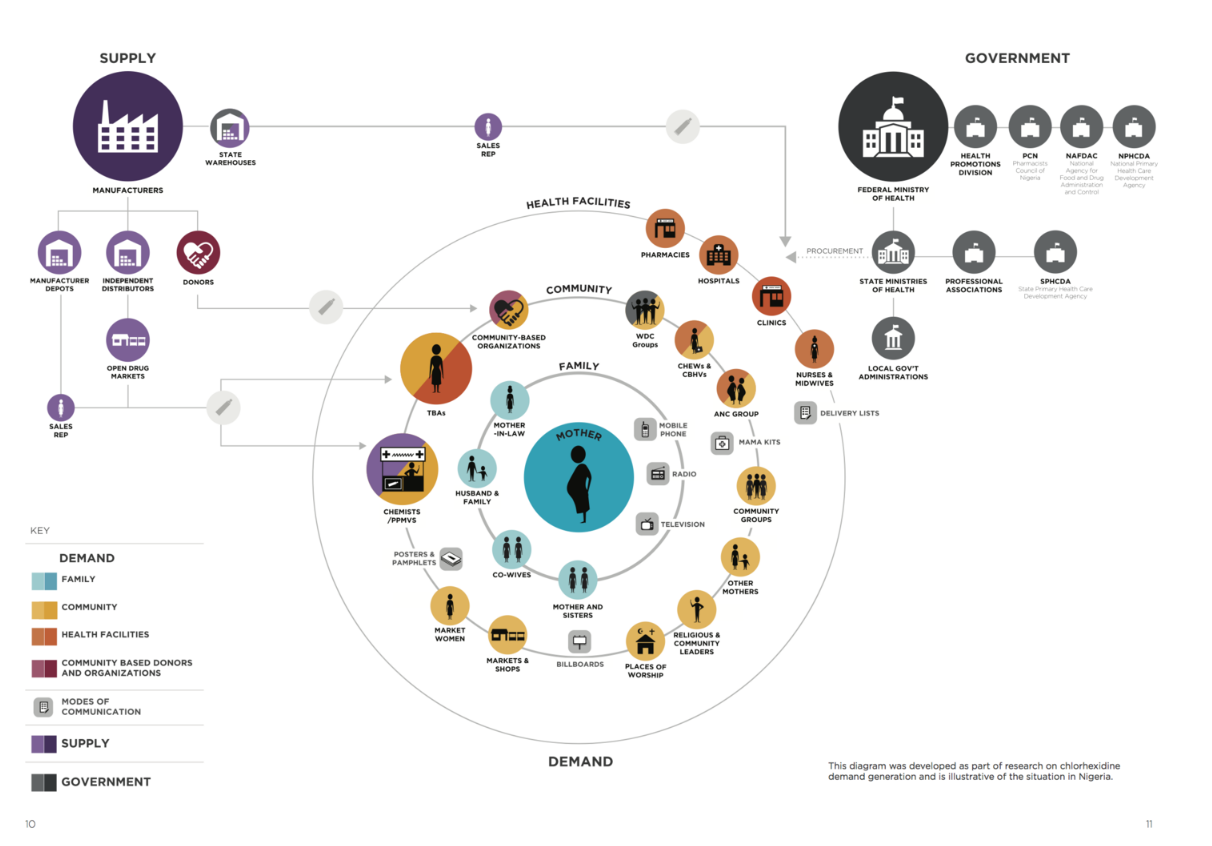

To understand Uwem and her challenges better, we mapped her network of relationships and influencers. Synthesized from insights from interviews, observations, and community visits, this map shows the relationships and systems that influence her, her birthing and purchasing decisions, as well as her newborn care practices:

CHALLENGE #1

EXPECTING MOTHERS STRUGGLE TO MAKE WELL-INFORMED CRITICAL DECISIONS IN THE FIRST DAYS OF LIFE FOR THEIR NEWBORN.

Some women are not sure when they need to come to the clinic and we don’t want them to go to a chemist instead. Many still lack information on how to decide between traditions and ensuring their health.” – CHEW, Kuchigoro, Nigeria

PROPOSED APPROACH:

Driving Demand for Chlorhexadine: A toolkit to raise awareness and drive demand for proper care practices in the first days of a child’s life. Nigeria has the second highest number of neonatal deaths in the world. Neonatal sepsis, combined with meningitis and tetanus, is estimated to be the third largest cause of neonatal mortality. The majority of these deaths could be averted through simple preventative practices such as clean skin and cord care given that poor hygiene during the first week of life significantly increases the risk of deadly infections. Current cord care practices in Nigeria are deeply entrenched in history and culture. DIG, along with our partner’s at USAID’s Center for Innovation and Impact (CII), conducted research in rural Nigeria to develop a toolkit for health systems — in Nigeria and globally — to drive demand for Chlorhexidine, an antiseptic used to treat the umbilical cord of newborn babies.

KEY FEATURES:

Behavioral Change Messaging: Encouraging the switch from current cord care substances to chlorhexidine by devising unique value propositions targeted to the population. We looked to the simple metaphor that chlorhexidine is a protectant just as in another commonly-found scenario in the community. For example, we developed a visual message based on a Yoruba proverb that compared fences which protect crops from animals to chlorhexidine protecting babies from infection.

Visual storytelling: Use of images, illustrations and photos to enhance existing tools, such as a ‘birth list’, or develop new ones. Images in the form of illustrations or photos are likely to be a valuable addition to the oral and written strategies currently used. Integration of chlorhexidine into the daily routine of caring for a newborn suggests the value of instructions that go beyond simply how to apply the gel. The addition of illustrations and images expands the relevance to the illiterate and semi-literate.

Service Design: A number of community-level concepts emerged from our time spent co-designing interventions with Nigerian communities. These concepts focused on ways to utilize the natural interactions within a community, particularly those in drug shops (PPP’s), with birth attendants, and in places where the general public and community leaders come together, for awareness and education about chlorhexidine.

Common Identifier: Design of a widely understood mark to signify chlorhexidine and its connection to cord care in newborns. As more chlorhexidine products enter the Nigerian market, messaging and packaging will become increasingly complicated as each manufacturer markets their product with its own unique name and brand. This insight led us to consider common identifiers – similar names, graphics, and marks shared across chlorhexidine products – that may address some of the issues around multiple brand identities.

CHALLENGE #2

EXPECTING MOTHERS NEED CONTINUOUS ACCESS TO INFORMED MEDICAL ADVICE OVER THE COURSE OF THE ANTENATAL AND POSTNATAL PERIODS.

Many people still lack information on how to decide between holding on to cultural traditions and ensuring their health and safety – midwife Amechi Idodo

PROPOSED APPROACH:

Exploring Application of Satellite-Delivered Health Content to Maternal Health Clinics: A model for bringing information into communities in support of new and expecting mothers. In peri-urban and rural communities in Nigeria, accurate information about maternal and child health is hard to come by for an expecting mother. Most women rely on traditional, intra-community channels such as word of mouth from friends or family, or community forums like the town crier, as a source of information. By leveraging the existing network of local, clinic-based medical professionals throughout Nigeria, we designed an information delivery service to bring the latest information and training content into information-poor communities, alongside our partners from the Praekelt Foundation.

KEY FEATURES:

Information Dissemination Strategy: Leveraging satellite technology to reach remote communities for low cost access to periodically-updated information from the web into communities that are otherwise cut off from ICT services. We took advantage of the human network and high-touch practice and training of local Community Health Extension Workers (CHEWs) to distribute this information into the community through a network hub at a select group of health clinics.

Content Media Library: Development of a library of existing content, prioritized for topics deemed most relevant and most impactful for local context, that can be cached and served locally over a wifi network at the clinic. Content is ideally presented through a variety of media, with emphasis on rich visual media such as video, which will address issues of language and literacy.

Digital Product Design: Creation of UX recommendations for a single digital product – an education and training module, designed for two distinct users: expecting mothers and healthcare workers.