Dalberg uses cookies and related technologies to improve the way the site functions. A cookie is a text file that is stored on your device. We use these text files for functionality such as to analyze our traffic or to personalize content. You can easily control how we use cookies on your device by adjusting the settings below, and you may also change those settings at any time by visiting our privacy policy page.

Caregivers are some of the most economically exposed workers inside the COVID-19 pandemic. Read on for what’s being done in the U.S. today — and how we can recognize the vital role these workers play in the economy, both now and in the future.

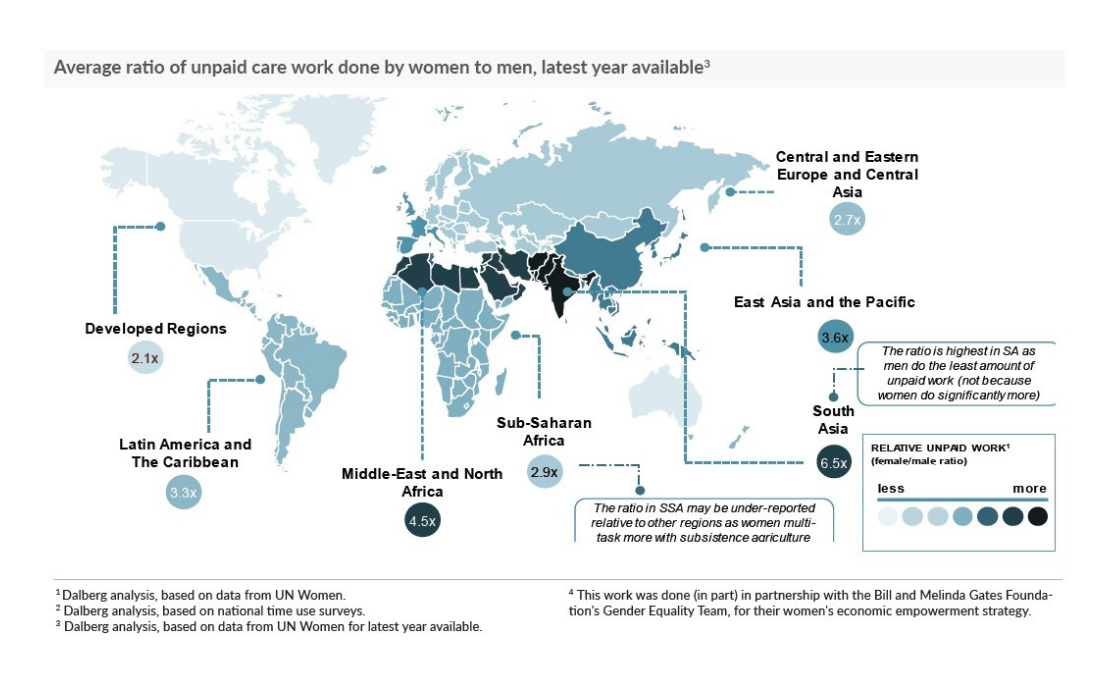

As the COVID-19 pandemic has developed, the ups and downs of telecommuting have come into clear focus. Online chatter is full of memes and articles that highlight the ways people are balancing paid work responsibilities with unpaid work responsibilities caring for children who are unexpectedly home from school or shut out of childcare centers. Women in developed economies like the U.S. still do nearly 2X more unpaid care work than men and are often the ones to take care of children when they are home from school, indicating that their burdens may disproportionately increase during this crisis.

Yet, while the new obstacles faced by women who are fresh to working from home are formidable, the more severe consequences of the pandemic are likely to be felt by the women on the other side of the care economy – the over 1 million childcare workers in the U.S., the majority of whom are female. Most individuals and businesses that earn their income from looking after others are now in a highly vulnerable situation. And in addition to these present-day social implications, the post-COVID economic situation could be significantly impacted if caregivers lose their jobs or move on to other lines of work.

A crisis for care workers

There are countless reports across the U.S. that social distancing guidelines and illness or fears of illness from both employees and employers are keeping individual caregivers from their work. Notwithstanding guidelines to keep some daycares open to serve essential workers, many have still shut down across the nation due to government mandates.

In a survey of 6,000 child care programs conducted this month by the National Association for the Education of Young Children, 17% of providers said that they wouldn’t survive any period of government-mandated closure without outside support and an additional 30% of providers said that they wouldn’t survive a closure of more than 2 weeks.

Women – and disproportionately, women of color and immigrants – make up nearly 95% of the childcare workforce, and 89% of childcare businesses are women-owned. These are the groups that will experience the broadest and most immediate impacts to changes in the care landscape.

What is being done today

So far, governments have largely taken the lead on solutions, but their efforts so far do not fully address the challenges faced by individual caregivers or childcare businesses.

On March 18, the federal “Families First Coronavirus Response Act” became law, which requires paid leave to be provided by employers. This is a positive step that ensures care workers diagnosed with or in quarantine for COVID-19 can continue to be paid. However, it will only apply to workers at larger centers with more than 50 employees – which is only 24% of all daycare workers – and does not cover individuals employed directly by families.

In California, the government approved $100M in emergency financial relief for K-12 districts and child care centers to cover cleaning expenses and ensure funding and pay for employees during closures. Yet, this only covers state-funded childcare centers and not private facilities.

A notable effort is an emergency relief fund by the National Domestic Workers Alliance to support affected domestic workers – yet its current goal is only to reach 10,000 workers. Other efforts across the country include agencies that are now trying to connect newly out-of-work individual caregivers with essential workers that must still work despite having children home due to school and other closures.

Keeping the caregiving economy running, now and in the future

Governments, philanthropic organizations, and private sector actors can take steps that both ensure workers are able to weather the acute crisis today and place them in a more sustainable economic position over the long term. Our ideas include:

1. Prioritizing small business assistance for care economy businesses – The success or failure of the care economy carries systemic implications. Across the U.S, research shows that access to childcare services has an effect on adult educational attainment, labor force participation, and earning potential, particularly for women. When families have support to look after their children, they have more time to be economically productive. Women’s labor force participation rates have grown in tandem with the size of the childcare industry in the U.S. An analysis of ‘child care deserts’ (areas in the U.S. with limited or no access to quality childcare) show that women’s labor force participation rates were at least 3 percentage points lower than women’s participation rates in areas with quality childcare. Results from the Current Population Survey in 2016 also highlighted that of workers that said they had to go part-time because of childcare problems, nearly 94% were women.

If a significant number of care businesses are no longer able to operate after the immediate crisis, the spillover effects could be felt in other industries for months and years to come and could negatively affect women’s overall ability to participate in the labor force. Therefore, there is a strong incentive to ensure efforts to provide near-term assistance to sustain small businesses in general (e.g., tax breaks, employment subsidies, and low interest loans) should be particularly prioritized for the care economy.

2. Extending post-crisis paid sick leave to more care workers – The provisions on paid sick leave in the new federal legislation can be an opportunity to create a new ‘normal’ in the industry. Instead of rescinding these rights for workers after the end of the crisis, state governments could expand local legislation such as New York’s Domestic Workers Bill of Rights to support substantive paid sick leave for these workers on a permanent basis. Similarly, childcare centers that are mandated to provide leave can choose to keep more generous policies in place in the long term.

Individual employers of childcare workers can utilize platforms like the National Domestic Workers Alliance’s Alia, which asks employers of domestic workers to contribute $5 per visit toward paid time off and insurance. Employer/employee matching services like Care.com and SitterCity can provide more education on standard benefits to be offered to employees and include tracking of sick leave alongside their ancillary services such as payroll tax support.

3. Supporting care worker organizing – Caregivers employed by individuals often need to navigate an unregulated terrain with varying standards and guidelines. More support networks and forums are needed that allow for exchange of information about rights and benefits. A handful of worker unions, cooperatives, and other initiatives already exist, and investments into and expansion of these forums will help these workers navigate the challenging times today and can set them up for needed support going forward.

As shocks to the economy ripple outward and expose the fabric of our social and economic systems, the essential role caregivers play will be more evident than ever before. This will present an opportune moment to recognize, through narrative and policy, the importance of these workers to the success of the broader U.S. economy.